Pakistan: Culture Revisited

Ten things we love about Pakistan Under the head, one in a collection of beautiful writings in theCritical Muslim issue 04 on Pakistan, the editors include People, Poetry, Classical Novels, Young Talent, Paklish (That is how English got decolonized in Pakistan), Ingenuity or the can-do attitude of the Pakistani people, Sweets, Mountains and Mangoes, Missiles, Load-shedding (‘Paklish for power cut and a metaphor for the efficient corruption of politicians). Why is it that of the ten things ‘we’ love about Pakistan, two are probably something that people from Pakistan don’t love about their country? For example missile, which symbolizes patriarchal military dictatorship (Syed Vali Nazr jokes, ‘Every country has a military; in Pakistan military has a country) and corruption may be the worst symbols that Pakistanis would like their country to be free from. Why is it that whenever we reflect on the country, the first images that creep into our mind are unpleasant?

Ten things we love about Pakistan Under the head, one in a collection of beautiful writings in theCritical Muslim issue 04 on Pakistan, the editors include People, Poetry, Classical Novels, Young Talent, Paklish (That is how English got decolonized in Pakistan), Ingenuity or the can-do attitude of the Pakistani people, Sweets, Mountains and Mangoes, Missiles, Load-shedding (‘Paklish for power cut and a metaphor for the efficient corruption of politicians). Why is it that of the ten things ‘we’ love about Pakistan, two are probably something that people from Pakistan don’t love about their country? For example missile, which symbolizes patriarchal military dictatorship (Syed Vali Nazr jokes, ‘Every country has a military; in Pakistan military has a country) and corruption may be the worst symbols that Pakistanis would like their country to be free from. Why is it that whenever we reflect on the country, the first images that creep into our mind are unpleasant?

Diplomats and journalists in the west have never ceased to imagine the country in the negative light. In fact, the west has never ceased to use the country as a launching pad for its nefarious designs in the South Asia. The country was the locus of the US hunting for al Qaeda and its project for ‘stabilizing’ Afghanistan. It backed Musharraf thinking that he will play in their hands and without realizing his own nefarious interest to play with the same fire that the terrorist lit. Always there was another Pakistan that the West did not project. There was a Pakistan of talented, upwardly mobile, educated, reform minded individuals. While playing the dangerous geo-political outswingers the west failed to bat for them. And at last, Robert Kaplan asks: ‘Should Pakistan survive? (Ziauddin Sardar’s: The Question Mark).

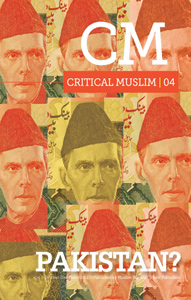

CM Pakistandoes try its best to offer a different picture of Pakistan from the one with which we are familiar from the western narratives. Using the latest trend of long-form journalism – in which long, in-depth articles are featured in the style of fiction writing – the issue tries to cover as much Pakistan as it can and brings to light its multi-faceted present. The book is divided into three sections. The first section is a collection of 13 articles on the most important areas and topics in the country. There are province-centered analyses such as ‘Karachi in Fragments’, ‘Quetta Divisions’, and Peshawar Blues etc. Also there are topic-centered writings such as Paperback Writers, Cock Studio, and Ibn Safi BA etc. The section features distinguished writers like Ziauddin Sardar, Ehsan Masood and Merryl Wyn Davies.

In the section Art and Letters, there are reproductions of two short stories and a poem which might lead readers to the fabulous wealth of Pakistani literature. The section features Atia Jilani ‘a self-taught calligrapher, a painter and a writer in the village of Muhammad Abad. She is the first Asian woman to inscribe the entire Quran in the elegant Calligraphic style of Naskh, despite never attending an art school.’ In the third section titled ET CETRA, there is an assessment as well as a critique of the one and only Imran Khan; the then things we love about Pakistan; the Pak comedian Shazia Mirza’s delectable writing about visiting Pakistan.

If one wants to make an assessment of the book, one needs only to go through Ayesha Malik’s photographs which run throughout the book. In the beginning we see a hapless, yet resolute rickshaw driver, the decorated trucks and bride that bear opulence and modesty all at once, the loneliness of an old man; children with innocence not smeared with any vestige of the turmoil around. These pictures, like Pakistan, don’t exude confidence of a thriving country. Faces of people bear the uncertainties of the landscape. Yet, as Zia sketches, ‘This Complex Pakistan has an abundance of intellectual and cultural resources that provide us with hope and inspiration.’

One of such resources brilliantly narrated in the book is the scenario of literature in the country. Ameer Hossein brings us to the amazing world of modern Classic Urdu fiction. In four pages, Ameer makes an autobiographic journey, introducing us to the gifted modern Urdu writers. In the second part, two Urdu short stories in translation give you a chance to taste the Pakistani fiction in its local variety. Muneeza Shamsie, mother of renowned Pakistani writer in English, writes in the article Discovering Matrix about how the mythologies or imaginariums (courtesy Merryl Wyn Davies) of Pakistan were handed from generation to generation through the gift of writing. Ziauddin Sardar’s piece on Ibn-e-Safi, BA, the Ian Fleming of Pakistan, is a delicious and brilliant piece of writing.

CM Pakistan is a page-turner while it keeps you informed and reflexive about Pakistan. Insights and reflections that the book offers make up for whatever is left out undocumented. Mehdi Hassan, Abida Parveen and Gulam Ali were all missing in its pages and Coke Studio’s mix of tradition and modernity has stolen the limelight. There is Pakistani cricket, which most Pakistanis take into their heart after oxygen. The world has learned Doosras and outswingers only after Pakistani bowlers experimented with them. All these talents of Pakistan could have added to the positives amidst the debris of desolation and war in the country. Still the book offers us an optimistic picture of the resolute, resilient and determined Pakistanis, who are capable of braving all odds.

Connect

Connect with us on the following social media platforms.