The Shadows of Muslim Men

A confession. In case you did not know I am a man. A generic, universal entity about which the seventeenth century French aristocrat Madame de Sevigne knew a thing or two. ‘The more I see of men’, she declared, ‘the more I admire dogs’. Knowing myself as well as I do, I appreciate her preference.

My gender has moulded the world in its own image. Everything from politics to finance, law to science, art and architecture, sports and entertainment are shaped, structured and led by men – and contain the fingerprints of masculinity. History is almost exclusively made by men; and it is always His story. Men hold a virtual monopoly in the corridors of power: whether in political institutions or banks, the judiciary or the media, universities or research laboratories, businesses or corporate organisations – anywhere where policies are made, decisions are announced, and all life on Earth is regulated. Not surprisingly, statistically men also perpetuate more crime than women, conventional as well as white-collar, from murders and killings, to football hooliganism, to nasty and greedy bankers ripping off the rest of society. The favourite pastime of men is, of course, war, perpetuated in the name of religion and ideologies but always focused on power and territory. And war imagery is integral to the sports that real men — that is ‘men with added man’, as an advertisement for chocolate milk playfully suggests — play: rugby, boxing, ice hockey and American football, which function as endlessly renewed symbols of war and masculinity. ‘Machismo’ is the foundation of most national narratives. Violence and men go together; and a great deal of violence, in this truncated half-human world that men have fashioned, is directed against women.

Worse: I am a Muslim man. So it can be taken for granted that I am a power hungry, frustrated misogynist, the archetype and ideal contemporary representative of what sociologists and geographers call ‘hegemonic masculinity’. Everything that Muslim men have produced, from scriptural interpretations to Shari’a Law to even our mysticism, is designed to keep women subjugated and isolated in a confined space. And our historic gift, patriarchy, ensures that things remain as they should. Even those who do not consciously enact their God-given right to hegemony (such as more liberal minded Muslims and enlightened scholars) receive the benefits of patriarchy.

Stephen Collins’ The Gigantic Beard That Was Evil brings in Dave-whose mammoth beard puts in disorder a land and people noted for neatness and perfection. Like Dave’s beard, the hegemonic masculinity of Muslim thought, exegesis, law, history, and piety is threatening to turn Islam into a wasteland.

From the women’s perspective, the history of Islam is not unlike the story of Dave, the protagonist of Stephen Collins’ wonderful graphic novel, The Gigantic Beard That Was Evil. Dave lives in a rather clean and sensible land, where not everything makes sense but people struggle to discover the meaning of life, called the island of Here. Then one day, he wakes up to feel a ‘roaring black fire climbing up through his face’ as his beard appears from nowhere. It is an extraordinary beard from a place far, far beyond the tidy and reasonably rational abode of Dave. And it grips Dave in a suffocating embrace. A bit like how Shari’a Law, based on the misogynist interpretation of the Qur’an and the life of Prophet Muhammad, is suddenly canonised in the ninth century and acquires a stranglehold on the Muslim imagination. Dave trims his beard all night, hoping to bring it down to manageable proportion, but at sunrise it is back to its mammoth and monolithic self. Soon it spreads everywhere and becomes a petrifying spectacle. The hairdressers of Here, working on scaffolding around the beard, are defeated. The police and the army try to contain it but to no avail. Soon the beard takes over the whole of the island Here. Other citizens start to experiment with their own beards, hairstyles and clothes. And an island that was once a neat and tidy place comes to resemble a bearded jungle. It becomes obvious that the gigantic, evil beard will kill its host. Like Dave’s beard, the hegemonic masculinity of Muslim thought, exegesis, law, history, and piety is threatening to turn Islam into a wasteland.

To appreciate what Muslim men are up to consider the events of a single day: Saturday 6 July 2013. Apart from the front page story, ‘Death toll grows as Egyptian factions fight in street’, my copy of The Guardian brought other important news. In Cairo’s Tahrir Square, where the anti-President Morsi protestors were gathered, there were 169 cases of assaults on women within a week: ‘we are talking about mob sexual assaults, from stripping women naked and dragging them on the floor – to rape’, explained a women’s right advocate. ‘In a typical attack, lines of men push their way through the square, surround alone women, and start ripping at their clothes until they are naked’, reports The Guardian. Some women were violated by men using their hands, others with sharp objects. The place where men were gathered to fight for ‘freedom’ is described by women as ‘the circle of hell’. One woman writes of her experience: ‘suddenly, I was in the middle, surrounded by hundreds of men in a circle that was getting smaller and smaller around me. At the same time, they were touching and groping me everywhere and there were so many hands under my shirt and inside my pants’. A few pages on we read the story of an Iranian woman, Elham Asghari, who, on a chilly winter’s morning, swam the Caspian sea in a ground-breaking nine hour feat. Surely an achievement to be celebrated! But even though she was covered from head to toe in ‘full Islamic dress code’, the authorities refused to recognise her record because, ‘the feminine features of my body were showing as I came out of the water’. And she lamented: ‘my record has been held hostage in the hands of people who cannot swim 20 metres’. Underneath this story, we have another one from Saudi Arabia, surely the most Islamic place in this best of all possible worlds. Under the heading ‘Saudi women activists fight jail threat’, The Guardian reports that two women are facing ten months in prison ‘for delivering a food parcel to a woman who told them she was imprisoned in her house with her children and unable to get food’. While I was reading through these stories, another story popped up around lunchtime: Boko Haram, a Nigerian brand of Islamists, had killed twenty-nine pupils and a teacher in a pre-dawn attack on a school in Mamudo town, Yobe state. The bearded and pious men of Boko Haram arrived with containers full of fuel and set fire to the school. Some children were burned alive, others were shot as they tried to flee.

During the anti-Morsi protests in Tahrir Square, women were reportedly beaten, harassed and raped. The place where men were gathered to fight for ‘freedom’ is described by women as ‘the circle of hell’. One woman writes of her experience: ‘suddenly, I was in the middle, surrounded by hundreds of men in a circle that was getting smaller and smaller around me. At the same time, they were touching and groping me everywhere and there were so many hands under my shirt and inside my pants’

Let’s beat around the bush a little. There are Muslim men who would argue that this is yet another example of the bias of the western media, which is hell-bent on demonising Islam and Muslims. Some other Muslim men would suggest that these are extreme examples, only fanatics and such sorts engage in these types of nefarious activities. Still others would point out, and rightly so, that not all Muslim men are like this. But I am not of these men. For me this is clear evidence of a culture gone pathological. Being an infinitesimally small part of the ‘western media’ myself – and I suspect just as biased – and reading these stories day after day, and having travelled extensively around the Muslim world, I am forced to conclude that the lunatics have taken over the asylum. And as a fully paid up member of the asylum I am obliged to put up my hand and declare: it is all my fault.

Lest you think I am being brave and original, I should add that I am simply following the example of a woman. The woman in question appears in Merryl Wyn Davies’ discussion on ‘The Problem of Men’. Some years ago, Davies addressed a meeting on ‘women in Islam’, a topic upon which she is often called to pontificate. ‘My presentation’, she writes, ‘attempted to get beyond the standard repertoire of the status, role and rights of women as idealised from Islamic sources and focus on what those ideals might mean and imply for living today in a globalised world, not Mecca in the seventh century or somewhere else long ago and far away in some imaginary Muslim society. A lively discussion ensued during which one lady who had been thoughtfully quiet for some time interjected. “It’s my fault I think”, she said. This seemed a rather large claim and onerous responsibility to take on. She went on to explain that she had raised sons and daughters and it was clear to her she had encouraged and enabled different standards for the boys as opposed to the girls. If there is a problem with Muslim men, and she was quite clear there was, then how she raised her sons, the kind of behaviour, expectations and attitudes she inculcated, permitted and tolerated were part and parcel of the problem. It was a brave statement to make, one that contains much truth to reason with. Mutual expectations are not conjured from thin air. How we interpret and apply our moral vision of society is what we can expect to see replicated.’

But what if ‘our moral vision’ itself is perverted? It is not just that the Qur’an has been largely interpreted by men. Nor that the Shari’a, which serves as both morality and law, has been socially constructed in history by men. Rather, many of the doctrines, institutions, and cultures of Islam are intrinsically masculine. Or to put it another way: the ideology of hegemonic masculinity has been the guiding principle of Islam in history and contemporary times. It is embedded in the thoughts, actions and practices of Muslims; and permits and continues Muslim men’s domination over Muslim women.

The problem starts not with men, but with God Himself, the deity invoked every moment of the day by every pious Muslim. It seems to me that Muslims have turned their God into a tribal leader – more specifically, a leader of the Quraysh, the tribe of the Prophet Muhammad. The Quraysh already have a mythical status in Islamic folklore. The Prophet, it is claimed, declared that ‘the leaders are from the Quraysh. The righteous among them are the leaders of the righteous, and the wicked among them are the leaders of the wicked’. So, if we accept this hadith as authentic, then Muslims are lumbered with the Quraysh for all eternity. A rather improbable task given that there are not enough of them to go around the globe. Since the Quraysh personify the best qualities of leadership, it is not surprising that the Ultimate Leader, the Creator of the Universe itself, is portrayed as though he was from the Quraysh. ‘This is a deity’, writes Abdennur Prado, ‘who judges, who is severe in punishment’, a vengeful, autocratic God who rules by fear and is without any attributes ‘except those that service goals of brute power’.

Given that fear, vengeance, and brute power are seen as the prime attributes of God, it is not surprising that they have become the dominant themes of Muslim societies. Without fear, Yusuf al-Qaradawi — seen by many as one of the most influential Sunni clerics in the Middle East — told his television audience: ‘if they had gotten rid of the punishment for apostasy, Islam would not exist today’. There is no moral qualm here; indeed, there is no notion of morality at all. To kill apostates is the most natural thing to do. It is after all part of God’s design and law. Al-Qaradawi’s sentiments would be echoed by conservative Muslim scholars from Saudi Arabia to Iran, Pakistan to Indonesia. And it is the same fear that is used to keep women in their prescribed positions.

Without fear, Yusuf al-Qaradawi — seen by many as one of the most influential Sunni clerics in the Middle East — told his television audience: ‘if they had gotten rid of the punishment for apostasy, Islam would not exist today.’ . Al-Qaradawi’s sentiments would be echoed by conservative Muslim scholars from Saudi Arabia to Iran, Pakistan to Indonesia. And it is the same fear that is used to keep women in their prescribed positions.

Of course, God has no gender; and His attributes reflect both masculine and feminine characteristics. As Prado notes, Muslim scholars have divided the Names of God into two categories: Names of Majesty, which reflect the masculine attributes; and Names of Beauty, which reflect the feminine attributes. Patriarchy has been entrenched, suggests Prado, by giving prominence to the masculine over the feminine attributes of God. And it has been further enhanced by the masculinisation of both the biography (Sira) and the examples (Sunnah) of the Prophet Muhammad. ‘The Prophet is presented as a political and patriarchal leader’, with ‘emphasis on military elements, conquests, and dominion’. The ulama, or the religious scholars, the historical counterparts of Al-Qaradawi such as al-Tabari (838-923) and ibn Kathir (1301-1373) and his contemporary colleagues, systematically read the Qur’an in patriarchal ways to establish ‘the primacy of the normative over the ethical, the judicial above the spiritual’. One particular tactic in masculine readings of the Qur’an involved imposing Biblical mythology on the Sacred Text. As Saleck Mohamed Val shows, male interpreters have systematically shrouded the Qur’anic text with Jewish and Christian traditions, known in Islamic terminology as Israiliyyat. So, for al-Tabari, Eve was to blame for the fall of Adam from Paradise; and for ibn Kathir, Eve was from Adam’s ‘left rib while he was asleep’. Of course, this alien imposition requires some local justification. So a host of truly misogynist manufactured hadith are cited to support this position, such as: ‘the woman was created from man, so that her desire would always be to him, while man was created from earth so that his desire would always be to it; you have then to incarcerate your women’. The end product is a doctrine that makes women innately inferior.

To ensure that the container of confinement is properly sealed, an entire body of law was developed to regulate and manage women. It was constructed almost as a confidence trick on behalf of men. In her contribution, ‘Out of This Dead-End’, Ziba Mir Hosseini provides a good example from the fourteenth century jurist Ibn Qayyim Jawziyya. While acknowledging that the Shari’a ‘embraces Justice, Kindness, the Common Good and Wisdom’, he nevertheless suggests that ‘the wife is her husband’s prisoner, a prisoner being akin to a slave. The Prophet directed men to support their wives by feeding them with their own food and clothing them with their own clothes; he said the same about maintaining a slave’. There is no connection between the premise and the conclusion; it seems the Shari’a is only kind and just to men.

In some cases, the jurists and the ulama resort to even more questionable tactics. Take the case of the prominent Syrian scholar Sheikh Wahba az- Zuhaili, who has written over a dozen books on Islamic jurisprudence and legal philosophy. The good Sheikh cites the following hadith: ‘Ibn Umar said: I saw a woman who came to the Prophet and said: “O Messenger of Allah, what is a wife’s obligation towards her husband?” Muhammad said: “Her obligation is that she does not go out of her house except by permission, and if she does, God, the Angels of Mercy, and the Angel of Anger will curse her until she repents or until she comes back”. She said: “And if he oppresses her?” Muhammad said: “Even if he oppresses her”. On the basis of this hadith, which provides a perfect justification for both misogyny and oppression, the ‘Dr Prof’ declares that ‘the woman is not to go out of her house even to perform the Hajj, except with the permission of her husband. And he (the husband) has the right to prevent her from going to the mosque and other places’. But there is no such hadith, or anything resembling it, in the six authentic collections, as Anne Sofie Roald, the Swedish Muslim feminist scholar, discovered after a long search. Az-Zuhaili also cites another hadith: ‘Verily the woman is awra (here: deficient). If she goes out, Satan will raise a glance at her. She will be closest to her Lord’s mercy inside the house’. Roald discovered that classical Muslim scholars did not accept this as an authentic hadith, as it has only one narrator and the chain of narrators is missing. Moreover, even in its original rejected form the hadith only contains the first part; there is nothing about staying at home.

Once the doctrine has been made manifest, a hadith has been cited for its justification, and the law canonised, there is nothing for women to do but obey a remote God who dictates His laws, and who has authorised the ulama as sole interpreters of His will and enforcers of His commands. The women themselves are constructed as a binary opposite of a mythological manhood: ‘hence the dominant idea of female sexuality in Muslim societies’, notes Prado, ‘as uncontrollable, a potential source of fitna (strife, sedition, rebellion) that must be tamed and appeased in some way’. This process consolidated ‘a specific type of masculinity: man as head of household, responsible for preserving the body and the honour of the women and providing for them; women, seen as weak and a source of conflict, are locked up indoors for protection and domestic chores’. This hegemonic masculinity is enforced in different ways by state institutions, such as constitutions, family law, gender relations, educational policies, dress codes, and even who can and cannot drive a car. ‘The end product’, writes Prado, ‘is the pre-eminence of a legal system focused on repression and the imposition of a perverted morality’.

About Ibn Qayyim Jawziyya, Ziba Mir Hosseini says: “While acknowledging that the Shari’a ‘embraces Justice, Kindness, the Common Good and Wisdom’, he nevertheless suggests that ‘the wife is her husband’s prisoner, a prisoner being akin to a slave. The Prophet directed men to support their wives by feeding them with their own food and clothing them with their own clothes; he said the same about maintaining a slave’. There is no connection between the premise and the conclusion; it seems the Shari’a is only kind and just to men.”

The logical conclusion of this process is men who are perpetually ready to defend their honour (by killing women if necessary), always keen to impose their version of Islam on all Others (by violence if necessary), and to keep the main source of fitna – women – in chains. At the apex of this hegemonic masculinity, according to Prado, are the Taliban: ‘The masculinity embodied by the Taliban is one in which the feminine has completely disappeared. All is determined by the reality of war and its necessities. There is no need for attentive and kind people, only ruthless warriors able to kill the enemy without flinching. For greater effectiveness, the enemy and everything associated with him is turned into a demon. It is a lifestyle with no notion of compassion’. I would also put Boko Haram, the Shabab of Somalia, and the jihadis of various ilks in the same category.

This lifestyle, which sees religion and politics as one and the same thing, has no place for ‘love, beauty, joy and pleasure’, which, writes Ziba Mir- Hosseini, ‘were all banished from public space’ after the Iranian revolution, ‘and anyone expressing them risked punishment’. It was all justified, as always, in ‘the name of Islam: it was God’s law, the Shari’a’. This combination of patriarchy and theological despotism has not only drained Islam of all sense of ethics and morality but also all notions of humanity.

One suspects that the recent cases of sexual grooming, abuse and exploitation of vulnerable teenage girls by Pakistani men in England is a product of the same lifestyle. During the last few years, eight different groups of Muslim Pakistani men have been convicted of sexual grooming in Oldham, Rotherham, Derby, Nelson, Telford, Rochdale and Oxford. Details in some of these cases are truly horrific, involving gang rapes, beatings, threats and passing girls from men to men. As Shamim Miah notes, ‘most of the perpetrators involved are married with children. Some are regular mosque goers; one was even a religious teacher in his local mosque’. Of course, these men are criminals, and criminals are to be found in all cultures and societies. They are paedophiles; and, it seems, paedophiles are crawling out of the woodwork like dreaded beetles throughout inhabited lands. So we cannot see this in terms of a specific race, religion or culture. We have to resist, as Miah warns, ‘the notion of the “Muslim sexual predator”, creating a new folk-devil’ that has been perpetuated by the British tabloid press. But two things cannot go unnoticed. These are all specifically Muslim Pakistani Men. Their religious and cultural context, which encouraged them to see young white women as ‘fair game’ who could be legitimately exploited, must have played some part in their nefarious behaviour. The way that some Muslims have justified this behaviour, blaming the women themselves and describing them as ‘uncovered meat’, hints that religion and culture are active players. Miah admits that ‘part of the answers lie in how women are perceived in certain Muslim circles’.

There is ample research to suggest that the notion of men’s honour and the shame that is supposedly associated with women’s very existence often lead to brutalisation of women in Muslim societies. For example, in Spaces of Masculinities, B van Hoven and K Horschelmann describe how men in Lebanon, challenged by the civil war, blamed the misery of war and urban life on women. Whether Shia or Sunni, the only way they knew of redeeming their war-torn honour was by exercising their rights as ‘protectors’ of women and thus ruthlessly repressing them. When you lose control in society, it is only natural that you should turn to the one place where you have the God given right to be ‘in control of your women’. A discourse was created that blamed a hated Other for their miseries, and the Other that became a punch bag for their frustrations was within their own families. When masculinity is defined both in terms of identity and ideology, humanity evaporates and all Others become fair game – including vulnerable white girls.

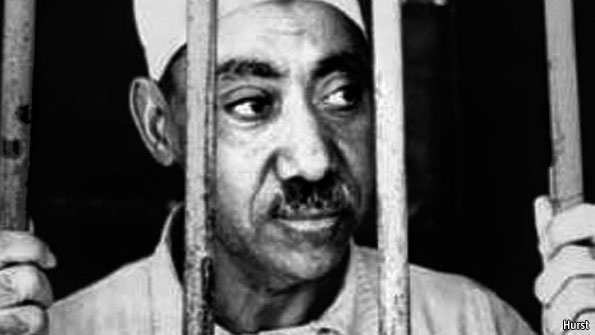

Of course, we should avoid the trap of essentialising Muslim men and their character, or imposing a false unity on a fluid ideology. Masculinity is not a fixed entity embodied in the personality trait of an individual man. Masculinities work as a configuration of practices that are accomplished in social actions and can differ according to particular social settings. Even ‘the Muslim man everyone is trying to describe as “the Islamist”, Tanjil Rashid points out, ‘is not made of Islam’, but is ‘a more complex composite of ideas and influences’. The particular Islamist in question is Sayyid Qutb, the ideologue of the Muslim Brotherhood, and surely the most influential ‘Islamist’ of our time. Qutb is credited with developing the takfiri ideology, the tendency to call other Muslims who disagree with you apostates, or kuffar (infidels). He had significant influence on al-Qaida, the Egyptian Islamic Jihad, and ‘the shrine-smashing Shabab today terrorising Somalia’.

But Qutb is a paradoxical character. During the 1930s, he was a progressive poet who saw constant recall to religion as ‘the battle-cry of the feeble-minded’. He went on to have a shining literary career as romantic poet, noted novelist, and respected literary critic who envisioned the present and the future ‘pregnant with possibilities outside the pale of the past’. He was first to spot the literary genius of the Nobel Laureate Naguib Mahfouz, who in turn gave glowing reviews to Qutb’s novels. He did more than anyone, writes Rashid, ‘to lend literary legitimacy to Mahfouz, but also did more than anyone to legitimise the insurgence that so menaced Mahfouz’. Mahfouz himself described Qutb as ‘a superb poet, story-teller and writer,’ who also ‘inspired the Islamic groups from whose ranks emerged the person who attempted to kill me. It’s a paradox’.

Sayyid Qutb’s misogyny is evident even in a much earlier and neglected work: Social Justice in Islam, which appeared in 1945. While ‘Islam has guaranteed to women a complete equality with women’, Qutb tells us, it is necessary for man to be ‘overseers of women’, to receive double the share of inheritance, and be the leaders and thinkers of society. The reason for this ‘discrimination lies in the physical endowment’ of a woman, who is ‘restricted for most of her life to family cares’. As ‘a man is free from the cares of the family, he can attend to the affairs of society’ and thus ‘apply to these affairs all his intellectual powers’.

His most influential work is Milestones, published in 1964, ‘a screed every bit as influential as Marx’s Manifesto, decreeing that “attacking the non-believers in their territories is a collective and individual duty”’. Milestones presents Qutb as a fully-fledged radical. However, his misogyny is evident even in a much earlier and neglected work: Social Justice in Islam, which appeared in 1945. It was translated in 1970 by the American Council of Learned Societies to create a ‘better understanding among American readers of the thinking and problems of Near Eastern people’. Here, Qutb presents Islam as a ‘universal theory’ of salvation based on ‘freedom of conscience’, ‘human equality’ and ‘mutual responsibility in society’. While ‘Islam has guaranteed to women a complete equality with women’, Qutb tells us, it is necessary for man to be ‘overseers of women’, to receive double the share of inheritance, and be the leaders and thinkers of society. The reason for this ‘discrimination lies in the physical endowment’ of a woman, who is ‘restricted for most of her life to family cares’. As ‘a man is free from the cares of the family, he can attend to the affairs of society’ and thus ‘apply to these affairs all his intellectual powers’. Women should concentrate on ‘emotions and passions’, while men devote their time ‘in the direction of reflection and thought’. Qutb’s character may be paradoxical but in matters of religion he was always unconventional.

Another man who commands almost as much influence as Qutb is the Turkish creationist Adnan Oktar, who writes under the rubric of ‘Haroon Yahya’. As Stefano Bigliardi points out, Yahya is a one-man mega industry devoted to promoting creationism, or what Val will describe as Israiliyyat, the Biblical account of creation. Ostensibly, Yahya aims to ‘demonstrate that Muslim faith is in harmony with science and compatible with a hyper-technological lifestyle’, a goal that appeals to generations of Muslim men in need of serious psychotherapy. The astounding global success of Yahya is a product of this mentality. But Yahya, as Bigliardi shows, has nothing to do with science. His wrath is directed against evolution which he sees as ‘the source of all the violent and repressive phenomena of the last centuries such as terrorism, totalitarianism, communism, fascism and racism as well as romanticism, capitalism, Buddhism, and Zionism (which to date he explicitly distinguishes from Judaism, after a flirt with Holocaust denial in the 1990s)’. They are all interconnected in Yahya’s view, and hell-bent on destroying the moral gendered order of Islam: ‘they all stem from and foster materialism, atheism, and pessimism’.

Like Qutb, Yahya is a paradoxical man. He is a great believer in science but knows nothing of how science works and devotes most of his efforts to disparaging one of its main theories – evolution. He promotes his creation¬ism but dresses it as science. While dishing out some pernicious nonsense for the simple-minded to lap up, he remains as romantic at heart as Qutb. In fact, all Muslim men are paradoxical and contradictory.

Like Qutb, Yahya is a paradoxical man. He is a great believer in science but knows nothing of how science works and devotes most of his efforts to disparaging one of its main theories – evolution. He promotes his creationism but dresses it as science. While dishing out some pernicious nonsense for the simple-minded to lap up, he remains as romantic at heart as Qutb. In fact, all Muslim men are paradoxical and contradictory. That’s the nature of human beings. Masculinities are always complex in the way they are socially constructed, produced, consumed and performed.

The problem arises when masculinities are analysed by looking only at men (a bit like what I have done!) and women are not considered as part of the analysis – what Davies would call a ‘faulty perspective’. All men are unique and diverse; and we can construct hegemonic masculinities that do not correspond to real lives of actual Muslim men. However, this does not mean that Muslim men do not, as a whole, contribute to hegemony and oppression of women in society. And it is not surprising those men who function as models of hegemony, such as Qutb or al-Qaradawi, or Mohammad Morsi, the former President of Egypt, exhibit contradictions.

The challenge is to move away from what Prado calls ‘perverted morality’ to ‘an ethic, a moral code that values the contributions of both men and women in their uniqueness and diversity’ that Davies argues for. But a new inclusive morality will only have meaning for Muslims if it emerges from within Islam and is based on Islamic sources. Our own sources, as Mir Hosseini argues, provide us all we need to challenge patriarchal interpretations of the Qur’an and Shari’a, and pull the carpet from underneath hegemonic notions of masculinity. Mir Hosseini, who has devoted all her adult life to fighting patriarchy, seeks ‘to engage with juristic constructs and theories, and to unveil the theological and logical arguments and legal theories that underpin them’. She narrates how her personal struggle led to the formation of, and her involvement in, Musawah, a movement that links ‘scholarship with activism to develop a holistic framework integrating Islamic teachings, universal human rights law, national constitutional guarantees of equality, and the lived realities of women and men’.

The journey must begin by returning to God and His Names of Beauty. Notions of masculinity in Muslim societies derived from the Names of Beauty have existed beside hegemonic ideals of masculinity. Prado shows how in the life of the Prophet Muhammad, or the ideas of ibn Arabi and ibn Rushd, we can find an alternative vision. Ibn Arabi, for example, argued that a man is not complete unless he has internalised the feminine; only then is he capable of actually receiving the Grace of God. A true believing man incorporates and inculcates the primary qualities of women such as compassion, nurturing, receptivity, and unconditional love. In advertising terms, we would call such men: ‘men with added woman’.

It would help if we had a better understanding and appreciation of the original and immense contribution made by women in Islamic history. Asma Afsaruddin suggests early Islamic history was shaped as much by women as men. Not only did women play an active part in society, they even influenced revelation itself. Afsaruddin recalls Umm ‘Umara, who observed that, up to that point, the Qur’an did not mention women. She told the Prophet: ‘I see that everything pertains to men; I do not see the mention of women’. As a result 33:35 was revealed, which ‘maintains the absolute religious and spiritual equality of women and men – no ifs or buts’. The verse states: ‘Those who have surrendered to God among males and females; those who believe among males and females; those who are sincere among males and females; those who are truthful among males and females; those who are patient among males and females; those who fear God among males and females; those who give in charity among males and females; those who fast among males and females; those who remember God often among males and females – God has prepared for them forgiveness and great reward’. Women also played political roles and had full citizenship rights in the early Islamic community. By making a personal pledge to the Prophet, they entered the Muslim polity as equals, and went on to be appointed as public inspectors and judges, and many, such as A’isha and Umm Salama, widows of the Prophet, transmitted prophetic traditions and were regarded as fountains of religious knowledge.

Ibn Arabi’ tomb located at at the bottom of Mount Qasyun in Damascus: The 13th century Sufi philosopher argued that a man is not complete unless he has internalised the feminine; only then is he capable of actually receiving the Grace of God. A true believing man incorporates and inculcates the primary qualities of women such as compas¬sion, nurturing, receptivity, and unconditional love. In advertising terms, we would call such men: ‘men with added woman’.

Much of this history is invisible because it has been written off by later historians – a process that continues to this day. In her razor sharp dissection of some recent contributions to Islamic studies, Kacia Ali shows how the process works. It is argued that the bar ‘of the super tradition of Islam’ is too high for women to reach, that women have to be ‘recognised’ as legitimate participants in discourse before their work can be considered, that women do not have large enough followings to be considered as influential thinkers, and by insisting that ‘the topic of women is too important to be dealt with briefly’ thereby deferring it perpetually. Eager to acknowledge the contributions of kindred spirits in history, ‘the omnipotent male scholar’ is able to produce a plethora of excuses to ignore and marginalise women. ‘Not only do people writing about Muslim reformers generally fail to take women seriously’, writes Ali, ‘so do reformers themselves’.

Ali is surely right to suggest that the right question that will take us forward is an epistemological one. Theological issues – deliberate misinterpretation, use of dubious hadiths, imposition of alien, aggressive masculinities on Islamic sources, and obscurantist arguments – have received ‘quite short shrift in Muslim feminist thinking’. But underlying these theological matters, and issues of legal and practical aspects of Muslim life, are epistemological questions: how do we determine what constitutes valid knowledge, what ways of knowing are possible, are there gendered dimensions to epistemology? ‘Does women’s personal experience play a role, and if so, what sort of role? How can experience be communicated and verified? How and when can one generalise from one’s own experience to say something broader about Islam, about humanity, about the world we inhabit?’

As I argued several decades ago in Islamic Futures: The Shape of Ideas to Come, the central challenge for Muslims is to rediscover a contemporary epistemology that emphasises the diversity and plurality of Islam, ‘the totality of experience and reality, and promotes not one but a number of diverse forms of knowledge from pure observation to the highest metaphysics’. We need to move away from a notion of masculinity that essentialises male-female difference and makes the subject invisible to a new, more inclusive idea of what it means to be a Muslim in the twenty-first century.

The formidable challenge to orthodoxy and traditional authority from Muslim feminists, such as Mir Hosseini, Kecia Ali and Asma Afsaruddin, has already taken the vital first steps towards a new ethics and morality in Islam. But it is not just the feminist scholars, largely located in the West, who are making original and ground-breaking contributions. Traditional female scholars in the Muslim world are also pushing the boundaries. The four scholars examined by Val – Aicha Abd al-Rahman (who wrote as Bint al- Shati), Zainab al-Ghazali, Fawkiyah Sherbini, and Kariman Hamzah – have done sterling work in an exceptionally difficult traditionalist environment. Indeed, just the fact that they are standing up to an oppressive tradition under repressive conditions to offer new readings of the Qur’an is worthy of awe and respect. Moreover, as Val notes, they cannot be dismissed for ‘flirting with patriarchy’ or labelled as ‘conspirators to their own subjugation’. And Val raises some important questions: ‘why have feminist scholars neglected these women?’ Why are certain feminist scholars, such as Amina Wadud, lionised, while the work of traditional female scholars looked down upon and dismissed ‘as a product of a patriarchal tradition’? It is not unusual for reformers, even women reformers, to end up constructing monolithic and exclusive enclaves.

To be inclusive we need to include all women in our discourse: traditional, modern, feminist, and those who do not subscribe to feminism – including women who were men. In her moving account of ‘not being a man’, Leyla Jagiella relates how she overcame bigotry and ‘conflicts surrounding my gender variant behaviour’. Jagiella was born a boy in a Protestant German family. Even as an infant, she felt like a girl with a male body. She had strong spiritual leanings from an early age, and embraced Islam as a teenager. As a result of her gender issues and conversion, she faced prejudice at school and at the mosque as well as problems at home. ‘My teenage years were spent in fighting simultaneously on different fronts’, she writes. Not surprisingly, she had ‘suicidal thoughts’. Then on her 21st birthday, during a visit to the shrine of Sufi saint Khwaja Gharib Nawaz in Ajmer, India, she decided ‘to start life as a woman’. Eventually she found solace not with the mainstream Muslim community, ‘not the most welcoming place’ for people who do not live up to ‘gender expectations’, but within the hijra (transsexual) community of India and Pakistan.

Kecia Ali, author of the works like Sexual Ethics in Islam and Marriage and Slavery in Islam says: “Eager to acknowledge the contributions of kindred spirits in history, ‘the omnipotent male scholar’ is able to produce a plethora of excuses to ignore and marginalise women.” ‘Not only do people writing about Muslim reformers generally fail to take women seriously’, writes Ali, ‘so do reformers themselves’.

Change can be external or internal. In Jagiella’s case it came from the inside; her ‘real self’ rebelled against the construction and restrictions of sex roles. If we wish to restructure gender roles in Islam, and dismantle hegemonic masculinities, we need to change Muslim men more than anything else. This is a task that requires us to stand up to our history. The trajectory of Islamic history shows that, with few notable exceptions, men in Islam have tended to exhibit a rather unsavoury variety of masculinity. Right at the formative phase of Islam, we find the famous ‘Story of Umm Zar’. It is said to be a hadith, narrated by Aisha, but is in fact more like a parable. A group of eleven women get together to talk about their husbands. The first one describes her husband as ‘a sort of the meat of a lean camel placed on the top of a mountain, which is difficult to climb up, and the meat is not good enough that one finds in oneself the urge to fetch it from the top of that mountain’. The second declares, ‘my husband is so bad that I am afraid I will not be able to describe his defects both visible and invisible completely’. The third one says, ‘my husband is a tall fellow. If he learns that I describe him, he will divorce me, and if I keep quiet I will be made to live in a state of suspense neither completely abandoned by him nor entertained as a wife’. And so it goes on in this fashion. One husband is foul mouthed and ‘suffering from all kinds of conceivable diseases’; another ‘eats so much that nothing is left back and when he drinks he drinks so that no drop is left behind, and when he lies down he wraps his body and does not touch me so that he may know my grief’. There are one or two decent men in this parable, but the one who comes out on top is Umma Zar’s husband, a wealthy individual who showers his wife with expensive gifts. But even he divorces her after meeting ‘a woman, having two children like leopards playing with her pomegranates under her vest’.

Leyla Jagiella blogs at http://leylajagiella.wordpress.com/2009/02/24/authentic-knowledge/

Jagiella was born a boy in a Protestant German family. A visit at the shrine of Mueenuddin Chisti at Ajmir changed her life, making him accept Islam and change the gender

Given this line-up, the burden of history is indeed arduous. Men in Islam, including the folks like me who think of themselves as liberals, cast a long and unhealthy shadow over the Muslim community. But cracks have begun to appear in this formidable façade. We all — men, women and those in-between — need to continue chipping away at the edifice of hegemonic masculinity until it collapses, in the hope that we can move forward to the warm, life-enhancing and generous sunshine of the liberating spirit of the Qur’an.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

(This article is reproduced with permission from the author and is published in Critical Muslim (Issue 08 : Men in Islam). Visit and subscribe to the magazine to read more)

Connect

Connect with us on the following social media platforms.