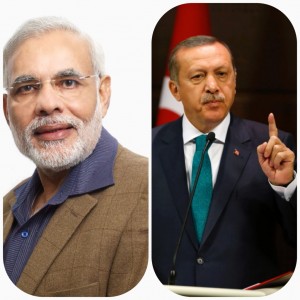

Erdogan and Modi: Parallel journeys?

Back in March 2013, when I received and accepted an invitation to visit Bogazici University, I did not for a moment imagine that my arrival in Turkey would follow hot on the heels of a historic election in India. But so it did: I landed in Istanbul on June 1, 2014, five days after the swearing-in of India’s new Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, of the BJP.

The outcome of the election, while not a surprise, was still a moment of reckoning for those such as myself, whose revulsion at the dynasticism and corruption of the Congress was outweighed by concerns about the BJP’s rightwing economic program and its espousal of majoritarian politics. The prime ministerial candidate’s record during his tenure as chief minister of Gujarat was itself the greatest of these concerns, especially in relation to his conduct during the anti-Muslim violence that had convulsed his state in 2002.

Before 2014, no Hindu nationalist party had ever won an outright majority of seats in India’s legislature. That the BJP had now come to power with a mandate far larger than predicted was clearly a sign of an upheaval in the country’s political firmament. How had this come about? What did it portend for the future?

It was only when I arrived in Istanbul that it struck me that Turkey had been through a similar moment 11 years before, in March 2003, when an election had brought in a new Prime Minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the founder of the Justice and Development Party (AKP). He too was heir to a long tradition of opposition to his country’s dominant secular-nationalist order; his party had also been closely linked with formerly banned religious organizations. He had himself been accused of inciting religious hatred and had even served a brief term in prison.

The margins of victory too were oddly similar: in 2003 PM Erdogan came to power with 32.26% of the popular vote and 363 of 550 seats in Parliament. In 2014 the coalition of parties headed by Modi won 336 of 543 parliamentary seats; his own party’s share of the vote was 31%.

Striking similarities

The parallels are striking. In both cases an entrenched secular-nationalist elite had been dislodged by a coalition that explicitly embraced the religion of a demographic majority. Secularism was itself a point of hot dispute in both elections, with the insurgent parties seeking to present the concept as a thinly-veiled means for monopolizing power and discriminating against the majority. But the ideological tussle over secularism and religion was a secondary matter: the winning candidates had both campaigned primarily on issues related to the economy and governance, promising to clean up corruption and create rapid economic growth.

The parallels extend even to biographical details. Erdogan was raised in straitened circumstances in a poor part of Istanbul; his parents were immigrants from the small town of Rize, on the Black Sea, and he had earned money in his childhood by selling ‘lemonade and pastry on the streets’. Modi was born in the small town of Vadnagar, in Gujarat, and as a child he had helped his father sell tea at the local railway station. Later, he and his brother had run a tea-stall of their own. Both men have been associated with religious groups since their early youth and both profess a deep personal piety. Both also have claims to physical prowess: Erdogan was a semi-professional footballer, and Modi has been known to boast of his 56-inch chest. Both leaders are powerful orators; both exert a charismatic sway over their followers and maintain an unchallenged grip on their party machinery.

his childhood by selling ‘lemonade and pastry on the streets’. Modi was born in the small town of Vadnagar, in Gujarat, and as a child he had helped his father sell tea at the local railway station. Later, he and his brother had run a tea-stall of their own. Both men have been associated with religious groups since their early youth and both profess a deep personal piety. Both also have claims to physical prowess: Erdogan was a semi-professional footballer, and Modi has been known to boast of his 56-inch chest. Both leaders are powerful orators; both exert a charismatic sway over their followers and maintain an unchallenged grip on their party machinery.

Mirror of history

This is by no means the first time that political developments in India and Turkey have mirrored each other. In the late 1960s and early ’70s both countries were shaken by left-wing student radicalism and trade union unrest. The next decade, similarly, was a time of deepening conflict between the state and minority groups: Kurds and Alevis in the case of Turkey; and Sikhs, Kashmiris, Nagas, Mizos and a host of others in India.

Between the years 1975-77 India went through a period of brutal repression under a State of Emergency imposed by Indira Gandhi; in Turkey the coup of September 12, 1980, led to mass imprisonments, torture and killings. In both countries the violence reached a climax in 1984: in Turkey an all-out war broke out between the army and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK); it was in this year too that the Indian army stormed the Golden Temple in Amritsar, which was followed by the assassination of Indira Gandhi and the massacre of thousands of Sikhs.

The parallels continue into the 1990s. In December 1992, an agitation launched by the BJP and its allies culminated in the tearing down of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya, by a mob of Hindu activists; this in turn led to months of rioting and thousands of deaths. In Turkey, in July 1993, a gathering of prominent Alevis was attacked by an Islamist mob in the town of Sivas: dozens of men and women were killed. In both cases it was the inaction of the authorities that permitted the violence to escalate.

The ‘liberalization’ of the Turkish and Indian economies also occurred in tandem, in the 1980s and ’90s. It was in these decades too that the secular-nationalist establishment of both countries began to suffer major setbacks, with religious parties steadily gaining ground.

That political developments in India and Turkey have occasionally mirrored each other is in some ways surprising, since the historical trajectories of the two republics have little in common. Unlike India, Turkey was never colonized; to the contrary it was itself a major imperial power until the First World War. In the second half of the 20th century, Turkey’s politics differed from India’s in that they were dominated by the army. As a close ally of the US, Turkey’s international alignments were also different from India’s through those decades. Perhaps more significantly, in material terms Turkey is (and has long been) far better off than India: its people are more prosperous and better educated, and its infrastructure is more ‘advanced’ in almost every respect. Indeed Turkey is effectively a First World country while India ranks in the lower levels of almost every index of ‘development’. Moreover India, with more than a billion people, is vastly larger than Turkey with its population of 77 million.

Salience of secularism

Yet the two countries do have at least one very important commonality: both are multi-ethnic and multi-religious, with very marked differences between regions. It is for this reason perhaps that the transition to nationhood was accompanied by similar traumas in both India and Turkey: indeed it could be said that it is in their dreams and nightmares, their anxieties and aspirations, that their commonalities find their most eloquent expression.

Both republics were born amidst civil conflict, war and massive exchanges of population. In no small part was it due to these experiences that secularism came to attain an unusual salience in the two countries: it was considered indispensable for the maintenance of peace and equity within diverse populations. But secularism was thought to be indispensable also to the aspirations for material advancement that lay at the heart of the Kemalist and Nehruvian projects. For the elites of both countries there was little difference between ‘secularism’ and ‘secularization’: the ultimate aspiration was for a general progression towards what Nehru liked to call the ‘scientific temper’. This was thought to be essential to the attainment of modern ways of living, as exemplified by the West. But since religion plays an important role in the lives of the vast majority of Indians and Turks, secularism was always an embattled aspiration, in both countries. Yet, through the latter decades of the 20th century, even as the banners of secular-nationalism were beginning to look increasingly tattered, their bearers somehow managed to retain their hold on power in both Turkey and India.

This does not mean, of course, that religious parties never had any taste of power before the ascent of Erdogan and Modi. Just as Erdogan’s advent was presaged by two former Prime Ministers, Turgut Ozal and Necmettin Erbakan, so too was Modi preceded as PM by another leader of the BJP: Atal Bihari Vajpayee.

Why then did the elections that brought Erdogan and Modi to power seem so pivotal? In part it was because these elections had each been preceded by a tectonic shift in the political landscape; a development that was most notably evident, in both cases, in the collapse of the traditional Left. In Turkey this collapse came about well before the election of 2003. This is how Jenny White, an anthropologist, puts it: ‘In previous decades, the Turkish left had carried the banner of ideological resistance to economic injustice. But the left had fallen victim to a double knockout punch: the post coup military crackdown and the global decline of socialism. Both left- and right-of-center parties abandoned the terrain of economic justice for more global issues. Islamist institutions and party platforms took over the role of the left as champions of economic justice…’

A similar dynamic was at work in India ten years later, most notably in my home state, West Bengal, where a Left Front, led by the CPM, had been dominant for more than three decades. But in the latter years of its rule the Left Front had come to be seen as corrupt and subservient to moneyed interests. Its rupture with the class that had brought it to power — small and marginal farmers — was set in motion by an effort to bring heavy industries into the state. This resulted in a series of land disputes between small farmers and corporations: by intervening on behalf of the latter, the Left Front sealed its own fate. In the election of 2014 the left parties suffered a defeat so catastrophic as to all but eliminate them as a major factor in national politics.

But there was a break also in the nature of the support that Erdogan and Modi were able to mobilize: they both succeeded in extending their bases beyond traditional religious groupings. Erdogan, for example, was able to draw on the resources of the vast network of educational, social and media-related organizations created by Fethullah Gulen, a religious figure who is in many respects quite different from traditional Islamist leaders. So too was Modi able to enlist not just the old Hindu nationalist organizations like the RSS, but also a number of gurus, godmen and pundits who have recently risen to prominence. Among them are some who have created new constituencies of Hindu activists in universities, tech companies and the like. This enabled the BJP to counter some of the charges that had proved most effective against religious conservatives in the past: that they are obscurantist and old fashioned; that they are a hindrance in the march to modernity; and so on. Instead, the BJP (like the AKP before it), was able to turn the tables on the secularists: it succeeded in presenting itself as more modern than its opponent, being less statist, less corrupt and less tainted by the past. That the BJP’s Prime Ministerial candidate was a self-made man, not a dynastic scion, was frequently cited to suggest that he would bring a new dynamism to the country’s politics.

Religion in a new package

The similarities in these two political careers are such as to suggest that something more than coincidence is at work here, something systemic. Erdogan and Modi are men of their time and have both come to power by riding a wave of neo-liberal globalization: their rise is proof that an economic ideology, when wrapped in a packaging of religious symbols and gestures, can have a tremendous electoral allure.

The process by which the neo-liberal program was sacralized in Turkey has been described thus by the scholar Cihan Tugal: ‘Starting with its establishment in 2001, the AKP’s ideologues presented it as the expression of an economic shift, but they did so using a quite spiritual language. … Religious civil society… combined its forces to sacralize the AKP’s economic program. Without this spiritualization, neo liberalism could not be sustained.’

Or, as another student of Turkish politics has put it: ‘… greater access to global resources, wealth accumulation, and communication technologies has redirected ‘political Islam’ toward an increasingly rationalized, post-political manifestation of something that might be termed ‘Market Islam’.’

That this shift took longer in India than in Turkey is perhaps partly attributable to Hinduism itself: it is no easy matter, after all, to superimpose an ideology of ‘growth’ and consumerism upon a religion in which asceticism and renunciation are foundational values. But over the last two decades an emergent alliance of right-wing economists, revisionist thinkers and electorally savvy politicians and strategists has pulled off the seemingly impossible. Through a re-branding exercise of the sort that contemporary corporations are so adept at, they have successfully invented and sold a new product — ‘Market Hinduism’.

The irony — a terrible one for people of a genuinely spiritual bent — is that this ideology has the power to impoverish the religions that it touches, emptying them of all that is distinctive in their traditions. Instead it infects those religions with ideas that are not only ‘secularized’ but are also directly opposed to many of the values that have historically been cherished by every religion.

Surprises, good and bad

Are there any portents for India in Turkey’s experience of AKP rule? I believe there are.

The first lesson is that Modi’s tenure is likely to pose many surprises for liberals, left-wingers and others opposed to the BJP. As Cihan Tugal writes: ‘The first three years of AKP rule were a liberal’s dream. The party passed many democratic reforms, recognized the existence of minorities hitherto rejected by official discourse, and liberalized the political system.’

Just as Erdogan was able to distance himself from his predecessors’ posture in relation to minority groups, it is perfectly possible that Modi too will take a different stance towards some of India’s troubled regions.

Equally, there may be some surprises ahead for New Delhi’s security hawks. Just as the AKP’s former Foreign Affairs Minister (and current PM), Ahmet Davutoglu, was able to engineer some significant changes in Turkey’s relationship with its neighbours, Modi too may be able to alter the regional dynamic in southern and eastern Asia. There are signs already that under his leadership India’s relations with China and Bangladesh will take a different tack.

In matters of governance, it is generally accepted that Erdogan has been more efficient and effective than his immediate predecessors. It is quite likely that this will be the case with Modi as well.

But what of Modi’s core promises: growth and economic expansion? Here the 11-year time lag between Erdogan’s election and Modi’s may be of critical importance. Through Erdogan’s first term as PM, Turkey’s GDP grew at an average rate of 7.2%. But this probably came about because of a global upswing that happened to occur at a time when ’emerging’ economies abounded in low-hanging fruit. In India, too, the economy was expanding at similar rates in that period, under a Congress-led government. But after the global downturn, there has been a marked slowing of growth in both India and Turkey. It would seem that unlike Erdogan, who had the good fortune to come to power with a favorable economic wind behind him, Modi’s ascent has coincided instead with a strengthening downdraft.

What will happen if expanding expectations of growth are hemmed in by a tightening horizon of possibility? If the Turkish experience is any indication, the likelihood is that the attempt to pursue old strategies of ‘growth’ will become increasingly frenzied. More malls will be built and more public lands will be sold off; real-estate bubbles will proliferate, accompanied by revelations of corruption; the privatization of natural resources will accelerate, perhaps even leading to the sale of rights to rivers. At the same time, grass-roots opposition will be suppressed and every effort will be made to silence environmentalists. But only for a brief period will it be possible to get away with this. At a certain point people will push back, as they did in Turkey, during the Gezi Park protests of 2013.Indeed the one area in which there is certain to be headlong growth is that of protest — a whiplash effect, ironically, of the same neo-liberal wave that has brought the AKP and the BJP to power. For it is now evident that the very currents that send tsunamis of capital and information hurtling around the world also have the effect of throwing up sand-bars of protest, many of which self-consciously mimic each other. But governments have also been quick to learn: from Hong Kong to Seattle, Istanbul to London, the powersthat-be have found ways to contain and ultimately disperse these movements. As a result their principal effect is often merely to bruise the egos of whichever leaders they happen to be directed against.

to the sale of rights to rivers. At the same time, grass-roots opposition will be suppressed and every effort will be made to silence environmentalists. But only for a brief period will it be possible to get away with this. At a certain point people will push back, as they did in Turkey, during the Gezi Park protests of 2013.Indeed the one area in which there is certain to be headlong growth is that of protest — a whiplash effect, ironically, of the same neo-liberal wave that has brought the AKP and the BJP to power. For it is now evident that the very currents that send tsunamis of capital and information hurtling around the world also have the effect of throwing up sand-bars of protest, many of which self-consciously mimic each other. But governments have also been quick to learn: from Hong Kong to Seattle, Istanbul to London, the powersthat-be have found ways to contain and ultimately disperse these movements. As a result their principal effect is often merely to bruise the egos of whichever leaders they happen to be directed against.

When protests break out in India, as they surely will, how will Narendra Modi respond? Will he take a leaf out of Erdogan’s book and become more authoritarian and repressive? Will he retreat into Sultanish isolation? Will political pressures ultimately lead to a break between him and some of the organizations that helped to bring him to power (as has been the case with Erdogan and the Gulenists)? Only time will tell.

No matter what Modi’s response, the contradictions between neo-liberal promises of growth and the constraints of the environment will not go away. Not only will they cause domestic disruptions, they will also impinge, with increasing insistence, on matters deemed to be ‘external’. Thus has the AKP’s ambitious foreign policy been disastrously waylaid by events beyond its borders, most notably by a conflict that has, to a significant degree, been shaped by climate-change: the civil war in Syria, which was triggered by the catastrophic drought that began in 2008.

India, like Turkey, happens to be located in a region that is exceptionally turbulent, both politically and climatically. It is more than likely that this region will be susceptible to similar disruptions.

Indeed perhaps the most important lesson of the Turkey’s recent past is that the world is now entering a period of extreme volatility, when governments will be so overwhelmed by crises and firefighting requirements that they will be less and less able to implement coherent programs and policies.

Courtesy: The Times of India

Connect

Connect with us on the following social media platforms.