The Court Jester of Bollywood

Naseeruddin Shah is the court jester of Bollywood, the nickname of Hindi Cinema, which, despite being derogatory (meaning senseless imitation), it embraced in vigour. The reason why everyone else comes only second to Shah in being a wise clown is that unlike most actors in the Hindi cinema world, Shah is not a fool whose meager intelligence is somewhat compensated by bulging biceps and synthetic six-packs. He is well-read and has lots of experience from toiling on the streets of India (not a spoilt brat, so to say). Despite being 65, he is a young man- not on account of his pairing with Vidhya Balan in many films, but because of his readiness to learn the niceties of acting and his willingness to adopt challenging roles and to adapt to any conditions.

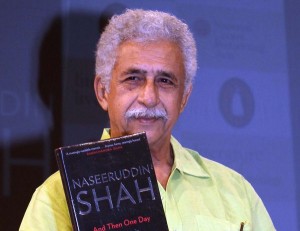

Nasreeruddin Shah’s memoir And Then One Day is all about the son of a civil servant, born one year after independence, turning inured to stage and screen on account of his inborn distaste for schooling and disciplines. In order to slowly arrive at the realization that acting was his calling, Shah had to uproot himself from the cozy, promising surroundings of his home and to cling to a life of toils and hardships. Rebellion was his forte and choice, right from the time he starts smoking in school, from visiting brothels in his college days, to staging protests in the film school.

To be a clown in the Bollywood is merely the consequence of his being a rebel there. He has spared no stars in the industry. But his diatribes against Bachchans and Khans are not motivated by jealousy of their stardom. Shah was primarily a man of theatre. “Films take you captive, they feed you everything on plate, the legerdemain they create transports you into a state where you may as well be dreaming, but theatre takes you into a world where your imagination is stimulated, your judgment is unimpaired and thus your enjoyment heightened.” His distaste for technology-induced celebrity value stems out of his nose for the stuff and worth of his calling. Also, he brushes aside all those that stardom offers: awards, money and celebrity status. “I began to loathe all competitive awards, particularly those which are an excuse for the film industry to indulge in its annual orgy of mutual jerking off.”

But it is to be asked why such a wise critic of the seedy underworld of celebrity-staffed Hindi cinema has acted in many films, though not as many as Bachchans and Khans did (like as many good ones as they did)? Why can’t he escape from those terms and conditions in the industry which make gifted and talented artists into money-making buffoons? This is because of that vital quality of a court clown which we find terribly missing in Shah (at least in the course of 316 pages of his well-written memoir): the amazing potential of self-criticism. Everywhere we see him attacking others from that pedestal of high art and we realize, with him being unaware, that the pedestal stands on the slough of the very industry he attacks. There is such a holier-than-thou approach in his critique that he appears to be hypocritical and that his words are not taken seriously (of course their humour aside).

However, there are many junctures in his life, as the memoir reveals, where he might as well be self-critical. According to this reviewer, the most crucial point is where Shah showers scorn on his ex-wife for being a fundamentalist Muslim without realizing his role in it. If a woman, whose husband does not visit her in the hospital where she is waiting for the delivery of their baby but visits, instead, brothels, prefers a fundamentalist as husband, she can’t be blamed. But self-criticism could have rendered Shah’s rebellion not only as more pungent but also as more effective.

Connect

Connect with us on the following social media platforms.