Towards an Islamic Decoloniality

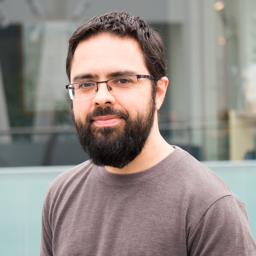

Dr Syed Mustafa Ali contributes to the robust academic-activist enterprise of decoloniality with his original ideas on Islamic decoloniality. Syed Ali teaches at The Open University in Milton Keynes (UK) as a member of the Faculty of Mathematics, Computing and Technology. The project of Islamic decoloniality he pioneered exposes various lacunae in leading decolonial projects the world over. He has a number of well-researched papers, monographs and articles to his credit, accessible at the click of a mouse. His diverse interests include ibn ‘Arabi, Martin Heidegger, decolonial computing. A few months ago, Syed Ali visited Calicut to deliver a keynote on decoloniality as part of the Muqaddimah Academic Summit organized by Students Islamic Organization. He shared his views on what he terms Islamic decoloniality in this interview with the then Interactive editor Shameer KS. This is the first part of the interview.

Syed, My questions are framed on the basis of your talks and interactions at Calicut as part of the Muqaddimah Academic Summit. You gave us all a newer perspective from which we can think about race and decoloniality. As it seems to me, the question of caste has helped you deepen your ideas. Now we are all thinking about caste in a more radical way after the suicide of Rohit Vemula, a promising Dalit research scholar suffering from multitudinous forms of institutional torture. De-colonial experience here means removing the structural violence meted out by the Brahminical power elites. That is something Dalit activists, including Rohit, have adopted from Babsaheb Ambedkar. For the latter, and for many intellectuals in his time – to cite Jinnah, for example – Eurocentrism had never been as problematic as Brahmin-centrism. My question is this: Can the spatial locution, suggested by Eurocentrism, be rethought as many temporal locutions of racist power in the praxis of the oppressed both in the east and the west?

Syed, My questions are framed on the basis of your talks and interactions at Calicut as part of the Muqaddimah Academic Summit. You gave us all a newer perspective from which we can think about race and decoloniality. As it seems to me, the question of caste has helped you deepen your ideas. Now we are all thinking about caste in a more radical way after the suicide of Rohit Vemula, a promising Dalit research scholar suffering from multitudinous forms of institutional torture. De-colonial experience here means removing the structural violence meted out by the Brahminical power elites. That is something Dalit activists, including Rohit, have adopted from Babsaheb Ambedkar. For the latter, and for many intellectuals in his time – to cite Jinnah, for example – Eurocentrism had never been as problematic as Brahmin-centrism. My question is this: Can the spatial locution, suggested by Eurocentrism, be rethought as many temporal locutions of racist power in the praxis of the oppressed both in the east and the west?

While it is, of course, possible to consider Eurocentrism as a particular or local site of enunciation of power – and I would suggest that realizing this possibility is basic to the decolonial project of de-centring or ‘provincializing’ ‘the West’ – I think it is important to recognise that the discursive power of Eurocentrism remains somewhat universal or global in scope. It is important to appreciate that by the latter, I don’t mean to imply that such power is totalistic, merely dominant or ‘hegemonic’ in some sense. In short, I think we need to commit to a somewhat paradoxical view of the socio-political reality of ‘The World’ wherein ‘the West’ is understood to be both universal and particular, thereby pointing to the persistence of Eurocentric ‘post-colonial’ structures of domination and the mounting contestation of such structures from various ‘subaltern’ sites of decolonial resistance.

As to the relationship between the ‘spatial’ and the ‘temporal’ in terms of locutions of racist power, I think it is important to be wary of the tendency to trans-historicize phenomena such as ‘racism’ (and related phenomena such as ‘colonialism’). Drawing on the ideas of decolonial thinkers such as Anibal Quijano, Walter Mignolo and Ramon Grosfoguel, I want to differentiate between three phenomena: (1) the ‘rupture’ of the pre-modern/pre-colonial world caused by the eruption of Eurocentric coloniality/modernity commencing in 1492 CE and continuing throughout the long durée of the 16th century – a global systemic phenomenon which is racially-inflected, (2) local manifestations of ‘racial’ / ‘racialized’ / ‘racializing’ phenomena occurring thereafter in colonial/post-colonial situations, and (3) purportedly pre-modern/pre-colonial ‘proto-racist’ formations. I also want to draw attention to the centrality of modernity/coloniality in ‘naming’ or classifying these phenomena, and the importance of thinking about time and history in terms of the body-politics (who, identity) and geo-politics (where, geography) of knowledge. Walter Mignolo has written extensively on this issue.

I would suggest that although ‘casteocracy’ – or what you refer to as Brahminical elite power – historically predates global systemic racism (white supremacy, ‘raceocracy’ etc.), the former is a geographically-particular phenomenon that has been integrated into coloniality/modernity as a sub-systemic component

On this basis, I would suggest that although ‘casteocracy’ – or what you refer to as Brahminical elite power – historically predates global systemic racism (white supremacy, ‘raceocracy’ etc.), the former is a geographically-particular phenomenon that has been integrated into coloniality/modernity as a sub-systemic component. I want to further suggest that casteocracy has been inflected by raceocracy / systemic racism, but that the former might also have influenced the formation of the latter; in this connection, I think the possibility of ‘entangled’ genealogies of the caste system in ‘India’ and the castas system in the ‘New World’ needs to be explored.

Having said this, I don’t want to give the impression that the systemic, global or universal is somehow more important than the sub-systemic, local or particular since that would arguably reproduce or re-inscribe a colonial structuralist account of knowing (epistemology) and being (or ontology); yet I also do not want to endorse a more Foucauldian post-structuralist position wherein power is taken to be exercised locally, both in dominant and resistant forms, at the expense of global or systemic manifestations of power. Once again, adopting a more paradoxical and ambivalent position, I suggest we consider both local and global power, perhaps prioritizing the former on tactical and pragmatic grounds but maintaining a strategic focus on the latter.

Put another way, it is not about replacing a local narrative of structural oppression with a global narrative of structural oppression, wherein the previously systemic is subsumed and becomes ‘merely’ sub-systemic from a global perspective; rather, the issue is one of understanding how the local and the global are related, both geographically and historically.

Would you elaborate on the idea of Islamic decoloniality as being a true alternative to decolonial thought, especially the horizontal and vertical structures? That was the crux of your talks in the summit and other forums. What are the problematic areas to be considered in many decolonial projects besides their alignment for practical purposes with the post-colonial elites who share the baggage of racism of the colonial past?

If by ‘true alternative to decolonial thought’ you mean a different way of thinking about and/or grounding the decolonial project, then I would suggest that Islamic decoloniality is precisely that insofar as I think decoloniality has tended to be framed with reference to the terms set by ‘secular’ – by which I mean post-Christian – frameworks that are genealogically-associated with and developmentally-informed by various ‘critical’ projects associated with the ‘left’; in this connection, consider area studies, world systems theory and postcolonial studies, all of which are inflected by strands of (post-)Marxist thinking. Although decoloniality continues to make moves in the direction of thinking ‘differently’ through peripheralised or ‘border’ logics and epistemologies – and this is central to the decolonial project – I am guarded about the extent to which colonial/modern logics remain operative, despite the trail-blazing efforts of decolonial scholars such as Walter Mignolo, Ramon Grosfoguel and Salman Sayyid; more precisely, I am wary that the terms within which the decolonial project tends to be articulated – at least insofar as this project relates to matters Islamic(ate) – have not been subjected to what might be regarded as a ‘second-order’ or reflexive decolonial critique. What I mean by this is that decoloniality itself might need decolonizing.

Islamic decoloniality is an attempt to effect such ‘second-order’ decoloniality – or decoloniality 2.0 – from a ‘site’, viz. Islam, which I consider paradoxically both ‘exterior’ and ‘interior’ to colonial modernity. What I mean by this is that I consider Islam to be both ahistorically-transcendent as well as historically-immanent in terms of its relation to the modern/colonial (and any other temporal or worldly) condition – that Islam has both ahistorical, transcendent or ‘exterior’ and historical, immanent or ‘interior’ ‘aspects’. This ‘dualism’ – or rather, complementarity – has a bearing on the distinction I make between ‘vertical’ or existential and ‘horizontal’ or institutional (social, political) transactional power relations which you have referred to as ‘structures’ above. Incidentally, this also sheds light on what I mean by ‘Islam’ insofar as I understand Islam to have a discursive tradition rather than be one; in this connection, my position contrasts somewhat with those of Talal Asad, Shahab Ahmed, Salman Sayyid and others, being closer to views articulated by S.M.N. Al-Attas and Eric Winkel. I am particularly interested in the possibility of endorsing, again paradoxically, both essentialist and anti-essentialist insights and commitments, thereby necessitating embrace of a post-Aristotelian ‘logic’ of both/neither. In this regard, I draw inspiration from the bazarkhian / izmuthic / ‘barrier’ thinking of ibn ‘Arabi who I consider to have been engaging in a kind of ‘border epistemology’ that complements the border logics of decolonial thinkers.

Islamic decoloniality is marked by a commitment to re-centering The Qur’an as something along the lines of what Eric Winkel refers to as a ‘Living Law’, where emphasis is placed on the dynamic and regulatory (or normative) aspects of The Qur’an, but also its plenitude vis-à-vis possibilities of meaning.

Islamic decoloniality, at least as I am attempting to formulate it, is marked by a commitment to re-centering the Qur’an, not as a ‘text’ as such, but rather as something along the lines of what Eric Winkel refers to as a ‘Living Law’, where emphasis is placed on the dynamic and regulatory (or normative) aspects of The Qur’an, but also its plenitude vis-à-vis possibilities of meaning. Islamic decoloniality is also about constructing – or perhaps extracting – an alternative ‘vocabulary’ (language, lexicon) for thinking through the decolonial project from an ‘Islamic situatedness’ (not to be confused with ‘Muslim subjectivity’), and again, The Qur’an is pivotal in terms of how I think this aspect of the project is to be informed.

In terms of ‘problematic areas’ to be considered in relation to decolonial projects, for me these have partly to do with what ‘language’ we adopt in framing the decolonial struggle, in other words, how we ‘talk’ or ‘discourse’ about it, but also how we think about the nature – or being (what-ness, how-ness) – of language itself in relation to (1) ‘the political’, (2) what I refer to, albeit problematically, as ‘the existential’ – that is, the relationship between the individual and God – and (3) the relationship between the political and the existential.

For example, in Islam and The Living Law: The Ibn al-‘Arabi Approach (1997), Eric Winkel distinguishes between lisaan-al-‘Arab and Arabic as follows: “The word Arab … refer[s] to that language which was used before and during the descent of the Qur’an. The later generations used a language I will call Arabic. The former language is fixed and transcendentalized by the revelation, whereas the latter is a growing, living language which incorporates concepts and world-views which are not necessarily Islamic [emphasis added].” (p.12) While I am prepared to accept such a dichotomy – and I think endorsing its validity is important in terms of differentiating between Islam, the Islamic and the Islamicate – I think we need to distinguish between the ‘fixing’ effected by the Qur’anic revelation as the speech (kalaam) of God, and the ‘fixing’ of terms afforded through the compilation of lexical canons. As an example of the former, consider Toshihiko Izutsu’s discussion in God and Man in The Qur’an (1964) of how The Qur’an forged – and, crucially, continues to forge – a link between taqwa and karam in (49:13), thereby pointing to what might be described as the ‘reconfiguration’ of semantic linguistic / discursive space – and, I would suggest, also existential space insofar as what this entailed was a change in ‘being’ in the sense of the meaning / intelligibility of practices and behaviours – resulting from the descent of The Qur’an. By contrast, insofar as the compilation of dictionaries and lexicons is a human venture, I suggest we consider adopting a ‘critical’ – or rather, following Rita Felski, perhaps a ‘post-critical’ – approach vis-à-vis the formation of canons such as that of ibn Mandhur and others – that is, considering what political, economic and other ‘background’ factors might have impacted upon the compilation of word meanings. However, rather than exclusively embracing a “hermeneutics of suspicion”, I think we need to engage also a complementary “hermeneutics of trust” (or faith); while the former provides an important check against unconscious tendencies to privilege human authorial voices in the direction of a tacit authoritarianism, the latter is consistent with both having a good opinion of other Muslims (that is, husn az-zann), and acknowledging what I take to be the ‘active role’ of God in protecting the Arab language insofar as the latter is a means by which to engage The Qur’an, the guarding of which God has taken upon Himself as stated in (15:9).

In this connection, I should point out that unlike those who have argued for the radical contingency of language and the arbitrary nature of the relation between signifier and signified – including a commitment to the view that this arbitrariness is temporarily ‘settled’ through the sedimentation of outcomes from historical struggles over meaning – I consider such accounts unsatisfying insofar as they appear reductively anthropic – that is, exclusively “human, all too human” – in nature, and ‘bracket’ other possibilities for semiotic / discursive agency including those that are limiting of the latter – for example, the Divine ‘regulation’ / ‘shaping’ / ‘contouring’ of language referred to earlier, at least insofar as the latter is ‘modulated’ by a revelation that is both the self-expression of God as well as one that is trans-historical (in the sense of manifesting across historicity). Put simply, I see The Divine as immanently ‘irrupting’ into each human speech act – sometimes to ‘permit’ (whether good or bad) and sometimes to ‘restrict’ (whether we are aware of such restriction or not).

‘Think of The Qur’an as a revolutionary text for decolonial thought as well as praxis’. That was another important point you brought home to us. But it requires teasing out further in the light of what many Muslims take to be what the text is telling them. One interlocutor asked you about anti-Semitism. Verses like (5:82) are cited by many Muslims, in the context of Zionist violence against Palestinians, to mean that The Qur’an is essentially pitched against Jews. Such verses as well as incidents involving historical groupings like Banu Quraydha are cited by Muslim intellectuals alongside Hitler’s SS (I mean Amin al Hussein’s Cream of Islam). Ibn Saud’s special envoy, Khalid al-Hud al-Gargani, cited the model of the Banu Quraydha expulsion for Hitler. How do you read the form of racism in Muslim thought in the parlance of racism you defined? How can we understand those verses and incidents afresh?

If my answer to the first question is correct regarding the historical uniqueness of Eurocentric coloniality/modernity as a global systemic phenomenon, then anti-Semitic phenomena of the kind mentioned above should be understood as colonially-inflected Muslim / Islamicate responses that are contextually-enabled. What I mean by this is that Muslim reactions to Zionist colonial settler-state violence are coloured (sic), to a lesser or greater extent, by the modern/colonial lens which has been shaped by an anti-Semitic legacy culminating in the Nazi genocide of European Jews and other ‘undesirables’.

Consistent with this decolonial perspective, I would suggest that the idea of The Qur’an being ‘essentially pitched against Jews’ is an uncritical, antagonistic, and trans-historical reading of both The Qur’an and Muslim / Islamicate engagement with Jewish populations, one that is readily undermined by consulting the historical record of such interactions in the pre-modern/pre-colonial era.

I suggest we combat unjust discriminatory practices by the Zionist state without mobilizing readings of The Qur’an that are warped by the modern/colonial encounter like the particular reading of the verse 5:82

At the risk of cliché and possible accusations of indulging in apologetics, when reading (5:82) and other verses (in fact, all verses), I think it is important to consider context. My approach to Qur’anic hermeneutics is informed by a number of commitments including taking seriously the contribution of three ‘contexts’, viz. (1) the historical context within which The Qur’an was revealed, (2) the contemporary context within which it is being read, and (3) the intra-textual context within which verses of The Qur’an are embedded; crucially, in relation to (3), I maintain that The Qur’an has both a linear (or sequential) and a non-linear (or network) structure. In engaging these three contexts, I am guided by an existential phenomenological reading of (41:53) and I think it is of decisive significance that this verse uses the plural of the word ayah (sign, indicator, message etc.) to refer to the signs of God in the horizons and within the selves of people, since this is the same word used for verses of The Qur’an. I am inclined to the view that this means The Qur’an, the horizons and the selves of people are ontologically the ‘same’ in some sense – that is, as ‘ayatic’ – and that they can, and should, be put into relationship with each other in order to generate ‘clarity’ (of meaning). This leads me to another hermeneutic commitment, viz. the importance of intra- and extra-textual tasreef, that is, inter-play of verses (signs, indicators etc.), as a means by which to generate such meaning. While my approach bears some similarity to the ‘double movement’ approach of Fazlur Rahman and the coherence (or nazm) approach of Amin Ahsan Islahi and others, and although it remains indebted to them in certain regards, I would argue it differs from both somewhat on account of its embrace of an existential phenomenological orientation and a commitment to linearity and non-linearity vis-à-vis textual structure. Recent sources of inspiration for thinking along these lines are the work of Iranian linguist and semiotician, Amer Gheitury, and the writings of ibn ‘Arabi as presented by Michel Chodkiewicz, William C. Chittick, Eric Winkel and others.

For this reason, I reject ‘atomistic’ approaches to The Qur’an involving trans-historical citation of isolated verses such as (5:82) devoid of contextual considerations – especially readings of this kind performed in the contemporary post-modern/post-colonial period where Muslims are subjected to various persecutory practices including Zionist violence and Islamophobia. I suggest we combat such unjust discriminatory practices without mobilizing readings of The Qur’an that are warped by the modern/colonial encounter, and that this requires us to engage more ‘critically’ in terms of how we read. In short, I am arguing for a decolonial – that is, contextual / historical – reading of The Qur’an, rather than an ahistorically anti-Semitic engagement with it.

Like anti-Semitism, ideas demeaning to women are current in the thought, talks and attitude of some Muslims. They cite the verse 4:34 as legitimizing Muslim men to beat women and as entitling them superior power over women. There have been hermeneutic attempts to interpret the verses. For example, Fazlur Rahman, Amina Wadud, Asma Barlas, Farid Esack – to cite a few scholars – adopted western hermeneutic tools to tease out the verses and interpret them from fresh perspectives. Saadiya Sheikh’s reading of Ibn Arabi is also relevant in the context. Without hermeneutics, to go directly back to The Qur’an appears to be problematic. But much of this hermeneutics, as you may perhaps think, originated in the Eurocentric matrix as in the thought of Gadamer and the phenomenology of Husserl. According to Professor Esack, there is nothing wrong in receiving ideas from the West. What do you think of this? How do you read those verses?

As to the specific issues of patriarchy, wife-beating etc. I broadly concur with the position(s) advanced by the thinkers you mention above and so have nothing of substance to add here in that regard.

Concerning the issue of receiving ideas from ‘the West’, rather than frame it in terms of ‘rightness’ and ‘wrongness’, I prefer to think about it in terms of the operation of power, and the consequences of receiving Western ideas under conditions marked by structurally-asymmetric power relationships. However, before looking at the possible effects of certain ideas, let me offer a brief comment on the matter of the ‘ownership’ of ideas.

During my Muqaddimah Summit keynote, I referred to a statement made in 1984 by the black feminist, Audre Lorde, viz. “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us to temporarily beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change.” While affording due recognition to the importance of this statement, decolonial scholar Lewis Gordon points out that it is based on at least two assumptions: (1) that the master’s tools are, in fact, his in the sense of originating with him rather than being appropriated by him from others, and (2) that only the master’s tools will be used to effect the dismantling of modernity/coloniality. The first point problematizes the genealogy of ideas, alerting us to the ‘cross-pollinating’ exchanges that have always taken place between different cultural and civilizational groups; the second point directs us to engage with the issue of ‘exteriority’ – that is, what ‘external’ resources, if any, are available to the decolonial project. (Of course, the very possibility of an ‘exterior’ turns on the question of whether modernity/coloniality is immanently totalistic – or ‘all-encompassing’ – a view that I reject on metaphysical grounds.)

“The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us to temporarily beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change.”

Audre Lorde

Farid Esack has drawn upon hermeneutics and the praxis of Latin American liberation theology to forge an Islamic liberation theology, and Salman Sayyid argues that postmodernism provides a set of ‘useful tools’ for decolonization as a precursor to forging Islamicate future(s). While I applaud such efforts, I remain somewhat concerned by what I perceive as a tendency within contemporary Muslim intellectual circles to assume that the ‘tools’ of ‘critical’ thinking – postmodernism, postcolonial theory, hermeneutics etc. – can be taken up and used to advance Muslim projects without incurring ‘costs’. I tend to think that this ‘instrumentalist’ outlook is problematic – assuming, of course, that it is, in fact, operative within Muslim intellectual activity, and I am not attacking a ‘straw man’ – because tools, theoretical or otherwise, have a certain seductive power and are associated with fetishizing tendencies; put simply, tools enchant and/or bewitch. Interestingly, I would suggest that The Qur’an alludes to such ‘seductive’ power when it states, at a number of places, that God has “made pleasing to every community their deeds”. The word ‘deed’ (‘amal), which is a noun, is derived from the same root as the verb form t’amaloona (‘you do’) used in (37:96). I think this is significant since Fazlur Rahman in Revival and Reform in Islam (2000), and before him Daud Rahbar in God of Justice (1960), argues that ‘you do’ should be understood as ‘you make’ – more specifically, ‘you carve’, the context being a discussion about idolatry. I should point out, however, that Rahman’s ‘modernist’ interpretation is at odds with the ‘classical’ Ash’ari and Akbarian readings of this verse.

Returning to the point I made earlier about reception under conditions of asymmetric power, it is important to appreciate that tools are made by people, and thereby reflect the ‘worldview’ of their creators insofar as the ‘background’ epistemology, ontology, axiology etc. of the latter is embedded into the design of such entities. While I would not want to argue that such ‘embeddedness’ precludes the possibility of subverting tools – that is, appropriating them for ends or projects other than those intended by their builders – I want to sound a note of caution against their being so readily adopted, often in what I consider to be an insufficiently ‘critical’ manner, and the need to attain and maintain heightened awareness and guardedness – what The Qur’an refers to as taqwa – in relation to the ‘dark power’ of tools emerging from the ‘dark colonial underside’ of modernity.

Finally, I am not advocating going ‘directly’ back to The Qur’an, although my position might be regarded as a ‘critical Salafism’ of sorts, notwithstanding the unfortunate connotations of the latter term in the contemporary period, insofar as I want to re-assert the centrality of the Qur’anic ‘text’ vis-à-vis forging an Islamic decoloniality. However, I don’t want to be seen as dismissive of the Islamic(ate) tradition nor of hermeneutics; on the contrary, my project is largely informed by a concern to ‘question concerning hermeneutics’ (to borrow from Heidegger) – that is, to interrogate the soundness and usefulness of ideas drawn from contemporary hermeneutics and related disciplines for a Qur’anically-informed approach to Islamic decoloniality. While appreciating the importance of Esack’s reader-response and praxis-based liberation-theological approach, Salman Sayyid’s post-structuralist political approach, and other frameworks such as the discourse-theoretical engagement of Nasr Hamid Abu Zayd, I am inclined to think that such hermeneutic approaches need augmenting with ideas, methods and techniques drawn from the ‘exteriority’ that is the Islamicate intellectual tradition. In this connection, I find the writings of ibn ‘Arabi – including those dealing with specifically linguistic and hermeneutic concerns – of particular value and a resource that I suggest needs ‘mining’ and ‘repurposing’ in service of an Islamic decolonial project. For example, ibn ‘Arabi’s emphasis on the importance of paying attention to textual shifts in the use of pronouns and terms of address within The Qur’an – that is, the phenomenon of iltifat readily demonstrated in (18:79-82), for example – leads me to consider whether the different ways in which the human being is referred to in (15:26-33) – firstly, as insan, then as bashar – has something to tell us about the historical phenomenon of ‘anti-blackness’, and that it might provide the ‘mythopoetic’ basis for articulating an alternative Islamic decolonial account of this phenomenon to that offered by seminal decolonial thinker and activist, Frantz Fanon.

Connect

Connect with us on the following social media platforms.