‘Mystical is Hardly a Retreat from Political’

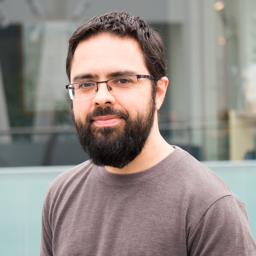

In an interview, outlining the salient features of the Islamic decoloniality project, Dr Syed Mustafa Ali calls out the matrix of colonial power which operates an insidious epistemology inflecting our ways of seeing and thinking. Syed Ali contributes to the robust academic-activist enterprise of decoloniality with his original idea of Islamic decoloniality. Syed Ali teaches at The Open University in Milton Keynes (UK) as a member of the Faculty of Mathematics, Computing and Technology. The project of Islamic decoloniality he pioneered exposes various lacunae in leading decolonial projects the world over. A few months ago, Syed Ali visited Calicut to deliver a keynote on decoloniality as part of the Muqaddimah Academic Summit organized by Students Islamic Organization. In this interview with Shameer KS, he discusses what he means by Islamic decoloniality and the future of thinking outside the colonial paradigm. This is the second part of the interview.

In various platforms in Calicut, you registered your reservations against intersectionality (the idea that all oppressive mechanisms such as racism, sexism, Islamophobia, xenophobia are interconnected and there should be common platform for the oppressed). Why should intersectionality be essentially problematic, given that Muslims don’t want to exert the same control over these identities as their oppressors do and Islam can allow space for polyphonic political assertions? Also, the truth value of the claims of sects like homosexual Muslims, which they made through reading The Qur’an differently, is for God to decide, isn’t it?

In various platforms in Calicut, you registered your reservations against intersectionality (the idea that all oppressive mechanisms such as racism, sexism, Islamophobia, xenophobia are interconnected and there should be common platform for the oppressed). Why should intersectionality be essentially problematic, given that Muslims don’t want to exert the same control over these identities as their oppressors do and Islam can allow space for polyphonic political assertions? Also, the truth value of the claims of sects like homosexual Muslims, which they made through reading The Qur’an differently, is for God to decide, isn’t it?

I see intersectionality in its contemporary mobilization as problematic for at least three reasons: firstly, it fails to consider the possibility – and, arguably, the reality – of local ‘reversals’ of certain oppressive mechanisms such as patriarchy; secondly, it has a tendency to ‘level’ – and thereby mask or erase – differences between oppressive mechanisms by abstracting what is said to be common to them – “they are all forms of oppression” – on the basis of analogy, thereby undermining arguments for prioritizing certain struggles relative to others. I appreciate that this is contentious since valorizing the matter of prioritization is a normative judgement, yet I would suggest that valorizing a poly-focal – you used the term ‘polyphonic’ – political orientation based on drawing analogies between oppressive mechanisms is no less normative; finally, and relatedly, I am inclined to the view that intersectionality tends to obscure the centrality of ‘race’ in what decolonial thinker Ramon Grosfoguel has referred to as the ‘entangled heterarchy’ of the colonial matrix of power – that is, the modern/colonial world. On this decolonial account, race / racism / racialization isn’t merely one oppressive mechanism intersecting with others; rather, it is the organizing principle of this systemic construct, non-reductively informing and inflecting all such mechanisms.

Regarding the issue of Islam ‘allowing’ space for polyphonic political assertions, I think that all turns on how one understands the operation of Islam in the sphere of the political and elsewhere: for example, does Islam refer (merely) to what Muslims do, or does it perhaps refer (also) to something else, viz. the basic ‘existential’ constitution of the cosmos including the human being as a ‘political’ entity?

I’m unaware that homosexual, gay or lesbian Muslims constitute a ‘sect’, however that term might be defined. That said, I uphold the ‘right’ of such groups to read The Qur’an, and read it ‘differently’ to contemporary orthodoxy; whether such ‘readings’ will gain traction in the Muslim community (ummah) is an entirely different matter, one that I don’t think will be settled – assuming, of course, that it can be – through purely discursive means. Furthermore, I think it is crucial to appreciate that the issue of Islam and ‘homosexuality’ is both complex and complicated by the entanglement of both under conditions of late modernity/coloniality. For example, as Foucault has shown, the very category ‘homosexual’ is a modern construction, and more recently, Joseph Massad and others have pointed to the mobilization of a ‘gay’ identity as a Eurocentric universal masking the operation of colonial power under liberalism. I think it is crucial to appreciate that there was no distinct ‘homosexual’ political identity in the pre-modern/pre-colonial Islamicate world, and consider the implications of this ‘lack’ in relation to contemporary gay, lesbian and queer politics.

As Foucault has shown, the very category ‘homosexual’ is a modern construction, and more recently, Joseph Massad and others have pointed to the mobilization of a ‘gay’ identity as a Eurocentric universal masking the operation of colonial power under liberalism.

Before listening to you, I saw readings of Sheikh al Akbar ibn ‘Arabi as marking him as an antinomian philosopher, except for the reading of Saadiya Sheikh. Many mystics and Sufis I know personally consider Akbarian metaphysics as a retreat from the political. You think of ‘political’ beyond ‘mystical’ when you cite him. Could you elaborate?

I’m not sure what sense of antinomian is being referred to here. If by this term is meant some kind of anti-legalism or dismissal of the necessity of obeying ‘the Law’ (that is, Shari’ah), then I think it is relatively straightforward to establish ibn ‘Arabi’s commitment to ‘legal’ fidelity, and this has been done by numerous scholars including William Chittick, Michel Chodkiewicz, but perhaps most explicitly by Eric Winkel in Islam and the Living Law: The ibn al-‘Arabi Approach (1997). (Incidentally, I think the term ‘antinomian’ is only problematically applied in an Islamic context given its Western Christian genealogy.) I have yet to engage with the work of Saadiya Sheikh, specifically her Sufi Narratives of Intimacy: ibn ‘Arabi, Gender and Sexuality (2012) which was kindly gifted to me during my stay in Kerala in December 2015.

I don’t recall saying that ‘the political’ was beyond ‘the mystical’, and it is not entirely clear to me what that might mean. What I have suggested is that it is erroneous to read the mystical and the political as being opposed to each other, and that Akbarian metaphysics might provide means by which to frame ‘the political’ otherwise than how it tends to be conceptualised by those following a Schmittian trajectory – I’m thinking specifically of Salman Sayyid here. I think Eric Winkel’s work, which I have mentioned above, is important in this regard insofar as it attempts to site the ‘political’ elsewhere – specifically, in the terrain of fiqh. (Interestingly, Hallaq makes a similar move, but I think his motivations are less informed by a commitment to tasawwuf.)

There is some historical evidence that ibn ‘Arabi advised the Ottomans with regard to the importance of blocking the incursions of crusader forces in Islamicate lands – hardly a retreat from matters ‘political’.

Vincent Cornell has attempted to mobilise Akbarian metaphysics in support of a liberal politics, but I would suggest that ibn ‘Arabi is more readily aligned with the decolonial project; in this connection, it is interesting to note that Eric Winkel has argued that Akbarian metaphysics provides means by which to effect a critique of patriarchy and racism, and others have shown that a commitment to an Akbarian ‘hermeneutics of mercy’ does not preclude the use of force – by which is meant ‘counter-violence’ – in pursuit of justice. I should also point out that there is some historical evidence that ibn ‘Arabi advised the Ottomans with regard to the importance of blocking the incursions of crusader forces in Islamicate lands – hardly a retreat from matters ‘political’.

However, my mobilisation of Akbarian metaphysics should not be understood as exclusive in the sense that I do not rely solely on ibn ‘Arabi’s thinking in formulating my conception of Islamic decoloniality; among other Sufi sources of inspiration, I am intrigued by figures such as Sidi Ahmad Zarruq who was what might be described as a ‘warrior saint’ insofar as he involved himself in politics and is an important figure within the Shadhdhilli order despite his not having associated himself with a tariqa and given a pledge to follow a sheikh of instruction. One can add to this list more recent figures such as Sheikh Usman dan Fodio who founded the Sokoto Caliphate, and the Chechen Qadiri Sheikh Shamil, both of whom combined commitments to the ‘political’ and the ‘mystical’. However, returning to ibn ‘Arabi, it is interesting to note that according to Michel Chodkiewicz, ibn ‘Arabi censured Mansur al-Hallaj for his ‘mystical’ detachment and failure to engage constructively in worldly affairs upon the basis of ‘mystical’ experience. It is for reasons such as these that I reject simplistic dichotomies positing an opposition between ‘the mystical’ and ‘the political’.

Two books you cite often are Salman Sayyid’s Recalling The Caliphate and Wael Hallaq’s The Impossible State, of which you like the latter for its bold analysis of state as an institution structurally rooted in the violence of Enlightenment and modernity. You consider, on that score, the idea of an Islamic state as being similar to halal pork. You consider Salman’s Sayyid’s thesis as being rooted in the new humanistic tools of postmodernity. What you propose is a kind of ‘anarchic’ revolution for horizontal restructuring and Islamic poly-verse? But is not anarchy a Eurocentric idea, as it is rooted in the thoughts of Marx and others? Has not Islam, since its very beginning, espoused a kind of political order like Caliphate, though it need not be state proper and has not many leading thinkers of Islam frowned upon rebellion?

Firstly, I should like to offer a few brief comments on my frequent citation of work by Salman Sayyid and Wael Hallaq, among others. While profound and provocative in its own right, the ‘Sayyidian corpus’, which includes A Fundamental Fear (1997) and his more recent Recalling The Caliphate (2014), but also his various essays, is ultimately of ‘negative’ importance for my own project. What I mean by this is that insofar as it constitutes perhaps a seminal attempt to engage philosophically with the matter of ‘Islam’ and ‘the decolonial’, Sayyid’s works have forced – and continue to force – me to attempt to think through, and hopefully clarify, the nature of the similarities and differences between our respective projects, viz. Islamic decoloniality and what he refers to as ‘critical Muslim studies’. Hallaq’s importance to my project is more ‘positive’ in orientation insofar as I tend to be persuaded by his critique of statist thinking vis-à-vis political organisation, and am broadly in agreement with the tenor of the recent ‘Qur’anic turn’ within his discourse. (I very much look forward to the publication of his forthcoming book, Re-Citing The Qur’an to Modernity.)

Since I have expressed my concerns about instrumentalist engagements with postmodern, postcolonial and other ‘critical’ tools already, I will confine myself here to addressing your questions about anarchism vis-à-vis the ‘horizontal’ Islamicate poly-verse.

While you are indeed correct to point out the Eurocentric genealogy of anarchism, some commentators have argued for the existence of non-European manifestations of ‘anarchism’ including those located within Islamicate history. For example, the Orientalist Patricia Crone maintains that certain ninth-century CE Mu’tazilites were committed to ‘an-archy’ – that is, belief in the dispensability of government or the view that Muslim society can function in the absence of the state. (She also attributes this view to one sub-sect of the Kharijites, viz. the Najdiyya.) However, it is important to point out that, according to Crone, the motivations for Islamicate ‘anarchism’ are quite different to those underpinning the Western anarchist tradition: the latter traces its roots to the Christian doctrine of ‘The Fall’ from an original state of innocence characterised by social living in the absence of domination and kingship; Muslim ‘anarchism’, by contrast, is held to accept the validity of coercive government, but is a response to the absence of its ideal form – that is, Medina under the rule of the Prophet and the first caliphs, who manifested a nomocratic form of government “between tyranny and anarchy” – and the emergence of dynastic imperial rule.

While it is true that Muslims have historically advocated the caliphate (or imamate) as the ideal political order, and a certain anti-rebellious quietist tendency, at least within mainstream Sunnism, did emerge over time – both of which

The Qur’anic account of the metaphysical caliphate which, somewhat paradoxically, I consider to be both pre-historical and trans-historical, has yet to be adequately engaged with in a political context in terms of the light it can shed on issues of power and domination

Crone endorses – I am interested in problematizing the link between Medina and the caliphate. To begin with, there is a need to distinguish two senses of the caliphate: (1) the caliphate as a ‘horizontal’ social contract between human beings, and (2) the caliphate as a ‘vertical’ personal contract between the human being and God. I maintain that while both senses of the caliphate appeal to the prophetic phenomenon, the former views it as a post-prophetic – more specifically, post-Muhammadan – institution, the latter as a pre-prophetic existential orientation, viz. the primordial and perennial ‘Adamic’ condition. Put simply, albeit crudely, we need to distinguish between a historical caliphate and a metaphysical caliphate, and I want to draw attention to the fact that The Qur’an – the founding ‘text’ of Islam – makes no mention of the former – that is, the institution – but does make explicit reference to the latter – that is, the existential orientation. I also want to point to the tendency to marginalise or ‘bracket’ the Qur’anic metaphysical caliphate from political-theological discourse and praxis, a development that I believe has impacted negatively on the historical character of the institutional caliphate in terms of what I perceive as a deviation from normative Islam.

What might result from establishing an institutional caliphate on a foundation other than ‘the legal’ or ‘the political’ – for example, on a ‘mystical’ basis? In saying this, and drawing upon what I said earlier, I want to challenge the assumption that mysticism – by which I mean tasawwuf – necessarily involves a pre-occupation with the transcendent or ‘vertical’ at the expense of this world and its immanent – ‘horizontal’ or ‘secular’ – concerns. On the contrary, I should like to argue that certain kinds of tasawwuf readily lend themselves to radical political action – including that which can result in the formation of an institutional caliphate – rather than quietist politics, and that there are many historical precedents in this regard.

In my opinion, the Qur’anic account of the metaphysical caliphate which, somewhat paradoxically, I consider to be both pre-historical and trans-historical, has yet to be adequately engaged with in a political context in terms of the light it can shed on issues of power and domination. I suggest that this account can provide a ‘post-secular’ basis for understanding the origin and nature of supremacism per se, and that it can – and should – be used to inform what might be described as an Islamic decolonial orientation against both Muslim supremacist aspirations of the ISIS and other varieties, and contemporary global white supremacy (or systemic racism).

While concurring with the mainstream Muslim view that Medina is both the ideal and formative location from which to think about the historical caliphate, I want to draw attention to the fact that The Qur’an is silent on the matter of the institutional caliphate – and according to some commentators, this silence extends to the prophetic Sunnah, although I appreciate this will be contested.

If we understand the Medinan polity established by Prophet Muhammad as a ‘state’ and the institutional caliphate as the continuation of this political formation, and yet if The Qur’an and Sunnah are, in fact, silent on the issue of ‘state’, how should we interpret such silence? Insofar as The Prophet himself established a polity, this would seem to point to the permissibility (ibaaha) of creating a state. But was the Medinan polity a state, and is the state a necessity? While the answer to these questions might appear to be a matter of definitions, I want to suggest otherwise.

If we think about this issue in terms of the ‘state’ in relation to the ‘secular’-‘religious’ divide – and I appreciate the latter is problematically applied in an Islamic context on account of its Eurocentric genealogy and relation to specifically Western Christian experience – broadly-speaking, I think there are, at the limit, four possibilities: (1) secular state, (2) non-secular state, (3) secular non-state, and (4) non-secular non-state. If we follow the first proposal, does this mean that ‘Islam’ and the ‘state’ should be kept separate, with the institutional caliphate understood as a ‘secular’ state in some sense, albeit one inspired by the religious and moral sentiments of Islam? Or, drawing upon arguments presented by Wael Hallaq in The Impossible State (2013), is it that the institutional caliphate is neither secular nor a state (at least not in the modern, centralised and monistic Weberian sense of the term), but a dawlat? By ‘dawlat’ I mean “a non-sovereign, non-territorial, temporary political arrangement that is accountable to and responsible for the whole ummat, not only to that portion of the ummat under its jurisdiction” as defined by Tamim al-Barghouti in The Umma and The Dawla (2008). Crucially, the actions of the dawlat are constrained by the Shari’a, which is both pluralistic and decentralised in production and application.

While I am broadly sympathetic to Hallaq’s position, I am interested in how it might be structurally-modified in order to address certain concerns I have about authoritarianism and imperialism, both Islamicate and otherwise; to paraphrase and invert Orwell’s famous line from Animal Farm (1945), I am inclined to the view that while “some empires are better than others, all empires are bad.”

Some commentators have pointed to the need for the restoration of an Islamicate ‘great power’ as the means to effect Muslim redemption in the political sphere; here I am thinking especially of Salman Sayyid. Although I am wary about “Games of Thrones” and “Ages of Empire”, I am somewhat sympathetic to this view. What interests me, however, is how we might think about the nature of this ‘great power’ by which is meant its organisation (or ‘structure’) and its normative orientation. For example, what if the prophetic and early caliphal ‘conquests’ were about ‘shutting down mega-machines’ (to borrow a phrase from Lewis Mumford), that is, dismantling imperial formations, and preventing their re-emergence? What if the task of this ‘great power’ is, in fact, to disperse political power, Islamicate and otherwise, such that the possibility of future ‘mega-machines’ arising driven by imperialist, colonialist, authoritarian and supremacist motives with aggrandizing power-centralising tendencies is reduced to a minimum?

So much for the orientation of this institutional caliphate. What of its structure?

Returning to the existential caliphate, I argue for maximizing freedom, autonomy, self-determination, agency and pluralism, and for minimizing the role of government – a ‘libertarian’ position of sorts that I argue is consistent with classical Islamic legal and political thinking, and suspension of which should be seen, normatively, as the exception rather than the rule. Incidentally, I think this raises interesting questions about where to site ‘the political’ which I have referred to earlier in connection with Eric Winkel’s position regarding the fiqh. If we can accept decentralisation and plurality in the fiqh, why not accept decentralisation and plurality in the implementation of imaarah (governance)? The Qur’an refers to ulul-al-amr – that is, those (rather than the one) charged with governing. Why assume that this refers to a historical succession of individual governors or rulers, rather than a spatial plurality of sites of governance? In this connection, it is interesting to note that early Muslim ‘anarchists’ advocated a number of proposals including complete dissolution of public authority, decentralization of power to local leaders, and the election of leaders to facilitate conflict resolution, arbitrate disputes – a role similar to that of the qadi as described in the writings of Winkel and Hallaq – and for purposes of defence.

More recent forms of Muslim ‘anarchism’ have tended to be articulated by Western – more specifically, white male – reverts including Hakim Bey (Peter Lamborn Wilson), Michael Muhammad Knight and the late ‘Abd al-Hakeem Carney, many of whom draw upon the Sufi tradition in order to articulate their position; however, it would be somewhat remiss of me to neglect drawing attention to the seminal work on Anarca-Islam by the Arab-Egyptian theorist, Mohamed Jean Veneuse. I should state that I have yet to engage properly with the arguments presented in such works.

In conclusion, I should state that my interest in ‘anarchism’ relates to the attempt to rethink the meaning of the institutional caliphate by returning to Islam’s founding ‘text’ – The Qur’an – in order to establish a minimal set of guiding ‘political’ constraints and commitments, and to de-sanctify what I take to be an increasingly hagiographic (that is, sacralised) Islamicate historical experience so as to be inspired by the past, not shackled by it; in short, a respectful and selective engagement with our tradition.

How do you differentiate the anarchy you vouch for from the kind of anarchy that terrorist movements like ISIS adopt?

I’m inclined to think there is a certain problematic slippage or conflation of violence with anarchy in the way you frame your question, and I would argue that ISIS is not anarchist, but rather radically statist in orientation – albeit a statism of a trans-national / non-national type.

However, that said, and as stated above, I’m not advocating anarchy in the sense of ‘absence of order’ or ‘chaos’. What I am pointing to is a condition in which governance is established ‘from the ground up’, rather than ‘from the sky down’; in

I would argue that ISIS is not anarchist, but rather radically statist in orientation – albeit a statism of a trans-national / non-national type.

this connection, I continue to draw inspiration from (14:24-26). As stated previously, I’m committed to the anarchist – or rather, libertarian – view that the best government is minimal government, a position that is consistent with ‘classical’ Islamic legal thinking on the issue of administrative politics (or siyaasa). Insofar as my position might be characterised, albeit problematically, as ‘anarchist’, it entails a commitment to post-statist minimalist government, and the establishment of a spatial plurality of sites of governance, self-organised in a ‘bottom-up’ fashion as some form of confederacy – what might be described as a radically decentralised self-organizing ‘caliphal network’. Unfortunately, in order for such a network to come into being, it will be necessary to dismantle the modern/colonial world order which, I’m sure you will appreciate, is no easy matter.

If I recall right, you don’t favour thinkers like ibn Sina and ibn Rushd as they followed the Aristotelian Neo-Platonism, which is a key ideology in the Eurocentric matrix. But the Islamic poly-verse you imagine includes them as glittering stars, doesn’t it? After Imam al Ghazzali’s revival of classical Islamic thought, Islamic rationalists like them have lost significance in Muslim thought and standard Islamic curricula. Now, be it Sunnis or Shi’ites, most of us think alike. Shabab Ahmad’s What is Islam? throws light on the issue especially noting why those thinkers matter. Your observations.

Firstly, although I don’t personally gravitate towards peripatetic philosophers such as ibn Sina and ibn Rushd, that shouldn’t be taken to imply any kind of dismissal of their seminal intellectual contributions to Islamicate thought and/or their abiding place in the Islamic poly-verse; for example, I’m aware that ibn ‘Arabi, someone from whom I draw much inspiration as already noted, who, while not a philosopher, mobilized certain peripatetic ideas, suitably re-interpreted, in articulating his own non-systemic metaphysics.

I’m somewhat wary of terms such as ‘Islamic rationalist’ insofar as the notion of ‘ratio’ associated with rationalism – and here we need to contrast ‘rationality’ with ‘intelligence’ in the Islamicate tradition – has rather Eurocentric Enlightenment connotations. In the introduction to On the Boundaries of Theological Tolerance in Islam: Abu Hamid al-Ghazali’s Faysal al-Tafriqa (2002), Sherman Jackson provides a useful problematization of the ‘rationalist’ / ‘traditionalist’ dichotomy. However, I appreciate the point you make about the relative absence of such ‘rationalist’ Islamicate figures from ‘standard Islamic curricula’, although I would want to caution against the possibility of a tacit universalization and reductionism that erases particularity and diversity.

I’m somewhat wary of terms such as ‘Islamic rationalist’ insofar as the notion of ‘ratio’ associated with rationalism has rather Eurocentric Enlightenment connotations. Sherman Jackson provides a useful problematization of the ‘rationalist’ / ‘traditionalist’ dichotomy.

As to Sunnites or Shi’ites thinking alike, I would say ‘yes’ and ‘no’ – concerns about universalization and reductionism notwithstanding. Insofar as Sunnites and Shi’ites are both situated within a modern/colonial world system that has impacted upon what it means ‘to be a Muslim in the world’ (to paraphrase both Esack and Dabashi) in terms of knowing and being, then I think you might be correct; however, I would suggest that the pre-modern/pre-colonial legacy of Islamicate sectarianism, originally political and later theological (and philosophical), persists under conditions of coloniality/modernity.

I have yet to engage the late Shahab Ahmed’s magnum opus properly. What I will say at this point is that I fully support his effort to make thinkers such as ibn Sina, ibn Rushd – and, especially ibn ‘Arabi – matter to Muslims again. Where I might disagree with him, and others such as Salman Sayyid, is that I don’t see the problem with contemporary Islam as having to do with ‘literalism’ and ‘legalism’ (or ‘law-centrism’). As Eric Winkel has shown in his short yet brilliant work, Islam and The Living Law: The Ibn Al-Arabi Approach (1997), ibn ‘Arabi is committed to both a fidelity to literal reading of The Qur’an and the centrality of Shari’ah, yet this ‘literalism’ and ‘legalism’ does not entail a reductionist or authoritarian approach to Islam, ‘the Islamic’ and/or Islamicate phenomena; on the contrary, it fosters both diversity and creativity, two features of the Islamic(ate) poly-verse that Ahmed (and Sayyid) endorse.

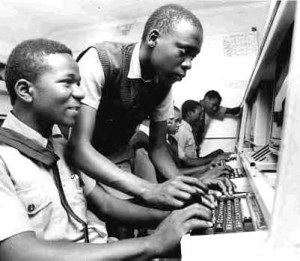

What about decolonial computing, an area in which you conduct research at the Open University. Could you say a bit more about that? My knowledge of that area has not gone far from Richard Stalman and his onslaught against Silicon Valley.

To begin with, I would suggest that Stalman is better understood as adopting a ‘critical’ or ‘Leftist’ stance rather than a decolonial orientation, at least on my formulation of the latter. This is not to belittle the importance of Stalman’s various contributions including the idea of copyLeft which he introduced in his GNU Manifesto in 1985, and his support for free software and resistance to surveillance; rather, it is to point to what I think is distinct about decolonial computing in relation to such ‘critical’ computing interventions, including the recent proposal of a ‘postcolonial computing’.

Drawing on the work of postcolonial theorists such as Edward Said, Gayatri Spivak and Homi Bhaba, postcolonial computing examines issues of culture and power at work in computing and ICT contexts including ICT4D, HCI and design methods and ubiquitous computing. While recognising the constructive possibilities associated with such a project, I think it suffers from a number of shortcomings which follow from its grounding in postcolonial theory which tends to focus on local cultural and literary phenomena at the expense of institutional structures of political-economy. In addition, insofar as postcolonial theory grounds itself in the post-structuralist ideas of Foucault, Lacan, Derrida and others, it thereby leaves itself open to the charge of co-option into a project of critical transformation that remains internal to Europe; in short, as decolonial scholars such as Walter Mignolo and Ramon Grosfoguel have argued, postcolonial theory ultimately constitutes, at least epistemologically, a Eurocentric critique of Eurocentrism. For this reason, I am inclined to think that we need to consider more radical forms of ‘critical’ engagement with computing and suggest decolonial computing as one such proposal.

I introduced the idea of ‘decolonial computing’ in a short conference piece entitled ‘Towards a Decolonial Computing’ in 2014 which is available on academia.edu, and an article on the same topic is scheduled to appear in the ACM student magazine XRDS shortly. In trying to think about what decolonial computing might mean, I want to begin by suggesting that the very idea of decolonial computing encourages the view that computing needs to be decolonised, and prompts us to consider how such decolonisation should be effected.

Human-computer interaction (HCI) theorists and practitioners such as Paul Dourish and Scott Mainwaring have pointed to the expansionist outreach of the phenomenon of ubiquitous or ‘pervasive’ computing (ubicomp) as driven by and exemplifying a ‘colonial impulse’; however, while endorsing the basic soundness of their argument, I think it is crucial to situate this specific development in relation to a more general ‘expansionist’ thrust of computing associated with an encompassing ‘background’ transformation of the modern world, viz. incessant ‘computerization’ and the rise of a global ‘information society’ following the ‘cybernetic turn’ associated with late modernity (i.e. the 1950s). I want to suggest that computationalism and the recent algorithmic ‘turn’ to ‘Big Data’, etc. point to something essential, albeit historically-essential, about computing as technological-modernity when the latter is viewed from its occluded, obscured and ignored ‘underside’, viz. not so much that computing has a colonial impulse, but rather, as decolonial thinkers might argue, that it is colonial through and through. Put simply, insofar as computing is a modern phenomenon and modernity is marked by coloniality, computing is colonial.

Decolonial computing is a response to computing’s colonial impulse. Grounded in a synthesis of the ‘oppositional’ critical race philosophy of Charles W. Mills, and the work of decolonial scholars such as Mignolo, Grosfoguel and Nelson Maldonado-Torres, decolonial computing attempts to ‘critically’ engage with the phenomenon of computing by thinking about it, as well as ‘doing’ it, from a perspective informed by, if not situated at, the margins (frontiers, borders, periphery) of the modern/colonial world system wherein issues of body-politics and geo-politics are analytically fore-grounded. Put differently,

Decolonial computing, is about interrogating who is doing computing, where they are doing it, and, thereby, what computing means both epistemologically (that is, in relation to knowing) and ontologically (that is, in relation to being). Decolonial computing foregrounds racial considerations, including the thorny question of reparations.

My most recent work in this area, grounded in earlier work exploring reflexive engagements between information theory and critical race philosophy, along with David Noble’s study of the ‘entangled’ relationship between religion and technology, Erik Davis’ exploration of links between magic, mysticism and information, and recent decolonial scholarship investigating the relationship between race and religion in the formation of the modern/colonial world system, together point to the need to expand the decolonial computing endeavour by including more explicitly ‘religious’ – that is, theo-political and/or ego-political – considerations within its remit. According to Vincent Lloyd, “race and religion are thoroughly entangled, perhaps starting with a shared point of origin in modernity, or in the colonial encounter. If this is the case, religion and race is not just another token of the type ‘religion and,’ not just one approach to the study of religion among many. Rather, every study of religion would need to be a study of religion and race.” Reflexively, I would argue that every study of race also needs to be a study of race and religion, and insofar as coloniality is necessarily tied to race, racism and racialization, and computing is a modern/colonial phenomenon, it follows that computing must also be considered in terms of its relation to ‘religion’. Here the work of Talal Asad, Saba Mahmood, Jose Casanova and William Cavanaugh on the relationship between ‘religion’, ‘the secular’ and ‘the post-secular’ looms large.

In closing, I should like to point out that as a very recent proposal at the fringes – or rather, periphery (borders, frontiers, margins) – of computing, decolonial computing is presently somewhat under-theorised. However, informed by a commitment to decolonial praxis and what might be described as an ‘open-source’ techno-political orientation – asymmetries of power notwithstanding – it invites participation in and contribution to its development while simultaneously being wary of co-option into the computing mainstream.

Connect

Connect with us on the following social media platforms.