Doyens of Letters No More

For readers of fiction, last few months have been the ones of loss. Here is a belated obituary of Gabriel Marquez, fondly called Gabbo, who created an alternative world, alternative Latin America so to say, which, with its wonderful mix of magic and the real, can give us an alternative to life ravaged by histories; of Pater Matthissen and his inward-outward travels which give us lessons on the significance of life as whole; of Khuswant Singh and his fearless, trenchant satire which ceaselessly ridiculed the smugness in which our blind faith in religion and politics clothed us…

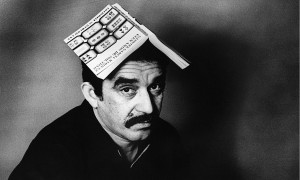

Gabriel Garcia Marquez (1927-2014)

What kind of novels would we like to read again and again? Are they the ones which depict the Hugovian or Dickensian world with the stark poverty on the street where the characters are forced to negotiate their way till end? Such novels do definitely have relevance. Because words purport to represent the world, realism is definitely the template with which most writers, especially the titans in the world of fiction, have been comfortable. None but VS Naipaul testified to the relevance of realism: The fantastic stands in place of enquiry, in place of facing reality. This whole thing makes me wonder about the Latin Americans, too, as if their writing isn’t, in fact, great intellectual fudge: avoidance of their calamitous history and of their corrupt rule since the Spaniards left.’

But however long one travels, however deeply one enquires, however brazenly one encounters the reality, one can’t be cent percentage sure. Only religious humbugs, cocksure moderns, and writers with I-will-teach-you-and-You-must-learn attitude can be sure of history and the lived life. Also, for those whom history gave nothing but harshness and cruelty, they can’t merely do justice to it by reviving the reality of self-abnegation. They have to create another reality on its stead and magical realism has opened the way out to the same. The pain of living in a loveless landscape can only be relieved by living a hundred years in solitude and waiting. Gabbo has taught us the worth of patience born of true love.

In his works like One Hundred Years of Solitude, Love in the time of Cholera and Autumn of a Patriarch, we can see a Latin America which honestly and openly embraces life-the tightly separated private and public ethos loosely commingle, thereby shutting out hypocrisy-and idealistically foresee a world where nothing but love reigns over all our concepts about living. Till he gave us bon voyage on April 17, he gave the surety of fictions on which we can rely amidst the tempests and temptations of the real.

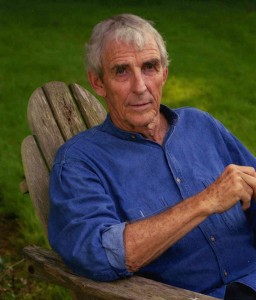

Peter Matthiessen (1927-2014)

Peter Matthiessen was the successor of Henri David Thoreau-if we go by his love of nature and wilderness and by his adroit fusing of naturalism with his diction. A brilliant career enriched by constant travelling, both inward and outward, and stunning experiences which include, as he later confessedly revealed, his being a CIA agent to the extent of using the Paris Review he co-founded as a cover (http://www.nytimes.com/2007/01/13/books/13hume.html?_r=0), saw the writing of novels which lovers of fiction always crave. He is specially noted, however, for the spiritual charm of a Buddhist that his non-fiction works, especially his travelogues exude. We keep living lives for our own sake with nothing to preserve for the generation to come, converting the whole nature and its resources as a grazing ground of greed-subverting thereby the Buddhist adage-‘live here and now’-into a pragmatic wisdom of capital-‘carpe diem.’ When he died of leukemia in April Mattiesson left for us a legacy of wisdom for a life to be lived in sync with nature. He better sums it up in these words: ‘The concept of conservation is a far truer sign of civilization than that spoilation of a continent which we once confused with progress.’ (Wildlife in America)

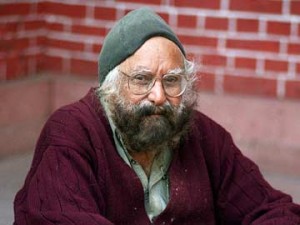

Khuswant Singh (1915-2014)

He is way beyond the Sardarji he caricatured in his delectable collection of jokes. He is not credulous, foolish or humorously adamant. He was, however, wily and knew how to effectively use the wiliness to the effect of Tamash. While being hurt, the victims at whom his words aimed could not help but boisterously laugh. He was a journalist and taught us the wisdom of reviving the dead, tired magazines by being aware of the needs of their readers. Though it was later much abused for sensationalism, it gave birth to a generation of magazines that ruffled the feathers of power centres and power brokers by fearlessly treading in the corridors of power, especially New Delhi, in search of expose.

He wrote his novels in view of the potential readership. His writing was always charming owing to a prose with hardly any convolution. It was as straightforward as the forceful push on a punching bag. Yes, he was a boxer while he wrote. He aimed at the humbug, pseudo-sophistication and the hypocritical middle class morality (represented by those readers of his The Company of Women only to discard it for bad taste) which, according to him, was generated by irrationalities out of our blind faith in religion and politics. He chronicled communalism which circulates in the vein of Indian polity as a harsh critique of the Indian self-confidence of peace and non-violence and promoted unconditional love among Indians and between Indians and others as a way out.

Till he departs on March 2014, he wrote 47 books spanning diverse genres of novel, short story, memoir, history etc. His translation of Allama Muhammad Iqbal’s Shikwa and Jawab e Shikwa is remarkable for the poetic beauty and the originality of employing apt metaphors in lieu of the original.

Interactive fondly remembers his Train to Pakistan while it does an issue on Pakistan. The novel recounts the gory moments in the history of India, when the country was partitioned with a trail of blood on all the north Indian streets. He brilliantly explains the attitude he formed forced by the events of calamitous proportions: “If you look at things as they are, there does not seem to be a code either of man or of God on which one can pattern one’s conduct. Wrong triumphs over right as much as right over wrong. Sometimes its triumphs are greater. What happens ultimately, you do not know. In such circumstances what can you do but cultivate an utter indifference to all values? Nothing matters. Nothing whatever.”

His writings might have been the creative outpouring of indifference.

Connect

Connect with us on the following social media platforms.