Leviathan and Winter Sleep: What Do We Believe

A believer needs to have patience as well as mirth out of facing a barrage of questions. So the one who helps a believer is often a non-believer. Only in the context of scepticism can a true belief grow. Linguist Toshihiko Izutsu says that belief is progression, not a state in which people find themselves in. That is the underlying difference between Islam and Iman.

The Quran narrates an event of Bedouins claiming they ‘believed’ and asks the Prophet to correct them by saying that they had not believed yet, but had just submitted (became Muslims) 49:14. Belief is graded above belonging to a group of believers. So belief is no more a condition than gradually increasing or gradually decreasing processes. Certainty out of witnessing and knowing truth through radically questioning and debating many of its circulated versions helps one raise the grade in one’s belief.

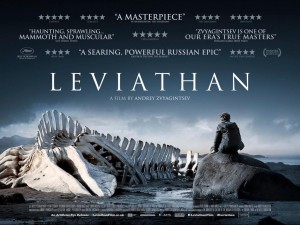

Two films released last year- Andrey Zvyagintsev’s Leviathan and Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Winter Sleep- make us take stock of the layers of ifs and buts as regards people’s belief in God. I am not saying that the two films made by ace auteurs, which were the centre of focus in the 2014 Cannes Film Festival (Leviathan bagging the award for best screenplay while Winter Sleep the very Palme d’Or), can be tethered to the questions of belief and non-belief. These films are much more than that. Leviathan overtly and Winter Sleep by way of allusions and symbolism engage the political and familial power structures. They are commentaries respectively on the Post-Soviet Russian and Post Kamalist Turkish suburbs. There is a tension created by transitions in power structure which however preserves the status quo in the everydayness of rustic lives. There is the promise of elite pleasures which the landowning middle class seek by leaving for either Moscow or Istanbul. Urban space thus becomes an apolitical utopia where there is less ‘overt’ control from the political, familial and religious power structures. But beyond all these, the point where the two films constantly guided my focus to was the discourse and narrative on belief scattered in the films throughout.

In his tract on political power, Thomas Hobbes was building a non-pejorative metaphor out of the denotation of the word leviathan as the largest and monstrous sea creature. In Hobbesian usage, leviathan is a civil as well as ecclesiastical form of power whose sovereign authority guides the social contract. We can’t help taking the leviathan for granted just as we do the air we breathe and the water we drink. But is the power or its political encapsulation in the civil and ecclesiastical states too harmless to be separated from the fearsome sea creature whose vestiges remain scattered around in the modern societies? Or, to put it more lucidly, is the state a surety of our living by a contract or is it an usurper of rights and security by cleverly and legally manipulating the contract? Zvyagintsev’s film tries to help us answer these questions by evocatively asking them. In the film throughout as well as in its posters, we see the fossil of a sea creature, helping us linking the metaphor of leviathan with its true, original denotation.

Leviathan is all about a Russian fisherman named Koyla’s (Alexey Serebryakov) fight against the municipal authority’s attempt to seize his property. He is failed in the courts and humiliated by recurrent tortures using fabricated cases. The municipal authority is the leviathan which, with the help of police and courts, dictates the terms and boundaries of Nikolai’s counter engagement. The larger picture emerges when we understands that leviathan is the mayor (Roman Madyanov) who is blessed with the ecclesiastical authority to go ahead with the project of usurping Koyla’s land. Koyla turns out to express the power he has in his home towards his wife (Elena Lyadova) and son, which further faces ruptures in his infidelity. While Koyla is bogged down under the baggage of allegations, including that of his wife’s death, the mayor can be seen taking part in the mass and being blessed by the priest.

What should people do, if they are forsaken by all authoritative trustees? What should they believe in, if the religious authority has become indifferent to them or has unleashed its billowing waves of power against them in such a way that it is a masquerade for leviathan? A devastated Koyla meets a local priest (not the one who keeps his tie with the mayor) and asks him where God is. “The priest quotes from the Book of Job: Can you pull in the leviathan with a fishhook or tie down its tongue with a rope? Nothing on earth is his equal.” He advises Koyla to adopt forbearance in the face of adversity like Job who, in the Bible, was harassed by the Leviathan-the king who wanted to usurp his vineyard. The priest here echoes the filmmaker’s didactic perception on a believer. Or is it an admonition that God does not reside in the power or in the church (or mosque for that matter) which craves political and sovereign power; He rather resides in the hope for the hopeless in the most adverse and hopeless situations?

Aydin in Ceylan’s Winter Sleep is a landowning hotelier who also lives on the rent collected from his tenants. A former actor and columnist, he advertises himself to be a man of conscience. He considers belief as a ‘tool’ for cultivating morals and values. Simply put, he is an urbane, luxury loving modern man apparently grappling with several contradictions. Though conscientious, he is indifferent to the travails of his tenants. He is scornful of the philanthropic activities his young wife Nihal (Melissa Sozen) has undertaken and his scorn is embedded in his misogynic and often irritatingly patronising attitudes. He is not reluctant to hurt the sentiments of his sister; yet he is not too open-minded to take her jibes at him. The traits of the vintage Turkish secularism are deep in his character as he prescribes what religion should be; yet he is a believer in his own estimates. His wife expresses his character much more evocatively: ‘Your high principles make you hate the whole world. You hate believers, because for you, believing is a sign of underdevelopment and ignorance. But you also hate non-believers for their lack of faith or ideals.’ The problem of neither being able to believe nor being a non-believer is quintessentially a modern condition. The problem is the one that a secular and modern self finds itself in when it tries to determine and define the contours of religion. It is charting out a way for believers to live, rather than posing questions regarding life and death, self and other etc, which would force all institutions and people to refresh their perceptions of truth and life. This has landed people in what Nihal identifies as a quandary of nihilism: (Conscience, Morals, Ideals, principles, the purpose of life. You’re always saying these words. The words you always use to humiliate, hurt, or denigrate someone. But if you ask me if someone uses these words this much, he’s the one to suspect.)

Winter Sleep poses the problem of conscience driving actions. It poses questions about the intention of humanitarian activities. Is it our sympathy or conscience for the poor that drives us to dole out a few liras to them, while exploiting them or being part of that exploitation.

It is in the void of questions we have to ask to ourselves, which perforce helps us attain certainty (yaqin), that we are forced to grapple with contradictions, disruptions, and self-deceptions.

Connect

Connect with us on the following social media platforms.